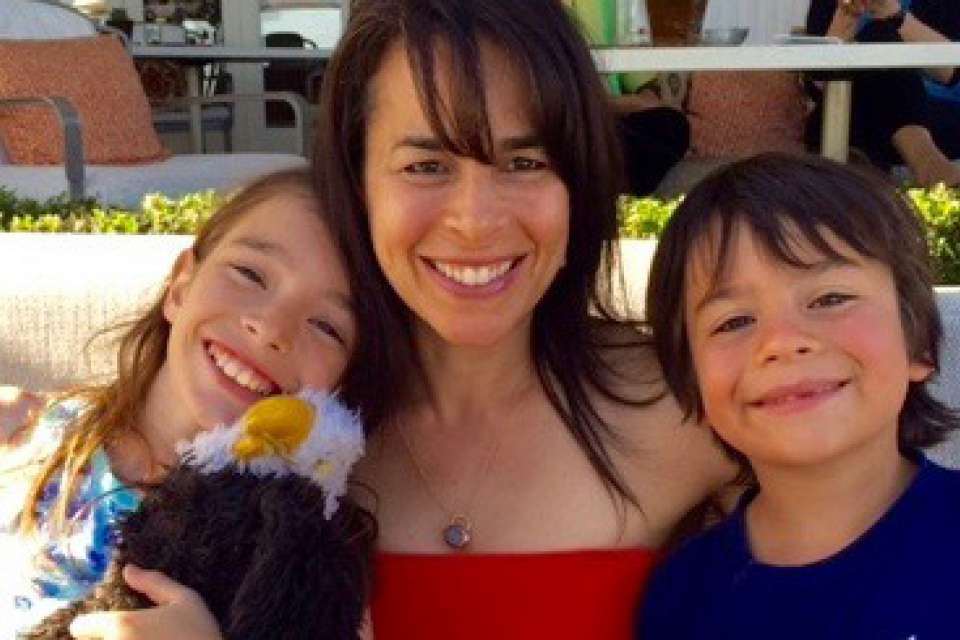

It was all in one day—her birthday—that Cynthia Kertesz, M.D., realized her life was going to change irrevocably. Her husband was a completely healthy 44-year-old who exercised regularly, ate well and didn’t smoke. But as they went for a hike together that day, she recognized that something significant was wrong. This is her story, as told to Vanessa Raymond.

A healthy 44-year-old should not have this symptom

For my birthday, my husband, Scott and I went for a hike together—one of my favorite things to do.

As we hiked, he was saying that he couldn’t believe I took him on such a difficult trail. It’s true that I was always more of a hiker but as I thought about what he said, I realized it didn’t make any sense.

We even saw a pregnant woman doing the same hike. It was just not as hard as he was making it out to be.

When we finished hiking, I noticed swelling in his legs. He had what is known as pitting edema—when you press the skin with a finger and it leaves an indent.

There are really only three reasons that you develop pitting edema—if something is going on with your heart or with your kidneys (or potentially your liver). As a medical doctor, I knew right away that this was bad.

And I knew that in some way, shape or form, my life was going to change.

From imagining the worst to living it

After we got back from the hike, we went to the doctor and found out he had nephrotic syndrome, which is evidence of damage to the kidney. So I started bracing myself for something big—like maybe a kidney transplant.

That would be a big deal, but I told myself we could survive it.

Two and a half weeks later we found out he had myeloma—one of many types of cancer that starts in the bone marrow. He had a particular type that caused amyloidosis, when a substance called amyloid builds up in your organs, and that’s what damaged his kidneys.

My kids were 4 and 6 years old at the time, and they were quoting me five to 10 years survival. It seemed like the worst thing in the world I could possibly hear.

And then three and half months later, he died.

Afterward, I couldn’t talk about it because I couldn’t function. Grief just wipes out your executive skills. And it’s not just your own grief you’re managing; there’s your children’s grief and your entire family’s grief all at the same time.

I had an incredibly supportive family, an incredibly supportive village, a wonderful employer. Even with all that, it took me two years to believe I was actually going to live through it. You have to deal with all these hard, terrible, complicated things at a time when you are the least equipped to handle them.

Our story might help someone else

I was so grateful that Scott and I had gotten our wills and life insurance together when we first had children. I don’t know how I would have survived without those things in place.

This is a kind of dramatic story, I know, but as we lived it, I recognized that I was in a unique position to share this experience with my patients. If there is anything good that can come of my husband’s death, I have to do it.

A unique kind of meet and greet

As a pediatrician, I do a lot of meet and greets—those meetings that patients set up with a potential pediatrician to learn about their practice and philosophy. I try to give people information that will be useful to them during these meetings. I think that’s what a pediatrician should do.

I tell new parents that having your first child is like crossing the Rubicon. There is absolutely no going back. You are now responsible for more than just your own life. You are responsible for a new life that you are choosing to bring into the world, and that’s a very big responsibility.

When my husband and I had our first child, we consulted financial counselors who gave us some good advice and I share that advice with my patients. I have a list of what you need to do and go through it with them.

Will. You need to prepare your will and figure out who will be the legal guardian for your child. Parents always want a say in the custody of their children. You want to be in the position to make that decision, not whoever happens to be left behind.

When I bring this up to patients, sometimes they tell me they don’t know who they want the kids to go to because his sister is a nightmare and so on. My point is that especially in those situations, you want to be the ones who make that choice. You don’t want to leave it to chance.

Creating a living will, which designates who can make your medical decisions if you aren’t able to make them yourself, is part of the will process, too.

Life insurance. You need to get life insurance. If you’re a solo parent, for yourself, and if you are raising children with a spouse or partner, for both of you, even if one of you stays at home.

If one of you dies, you need enough money to pay off the house and to cover your expenses for two years. It costs more than you can imagine to replace all the work that a stay-at-home partner does.

Sometimes people will say that they have life insurance through their work, and I’ll ask, “Just curious, how much do you have?” They will say something like $25,000. And I’ll say, “Good, that will get you through the funeral.”

I had no idea how expensive it would be to bury my husband and wade through all that needed to be done. It is far more than most imagine and not a time in your life when you are really able to cut corners, let alone be forced to sell your house or try to find a new job.

Documentation. You both need to have all of your accounts documented and written down. Where do you have retirement accounts? What kind of insurance do you have? You need to know the names and numbers of your accountant and your lawyer—people like that. All of that stuff.

Make sure it's in a place where if you die, your spouse can find it easily and if you and your spouse die; your brother-in-law can find it.

Relationship status. I push hard on the couples that aren’t married. If you’re with somebody but not married, especially if you don’t get along with their family, you can be excluded from every little bit of this process, including not being able to visit your partner in the hospital.

The less codified your relationship, the more you should document what your wishes are. After someone dies, it can get really complicated really fast.

Having a baby is a natural transition point and a good time to make all these changes.

Blunt but true

After a while as I talk about this stuff, I can see some parents’ attention kind of fading away. They’re nodding their heads, saying yeah, yeah, but they’re not really listening anymore.

Nobody wants to think about these things. I get that.

That’s when I say: This is not theoretical. This happened to me.

That gets their attention.

There are people whose partner is sick for years; there are people who wake up next to a dead spouse—it’s all just different flavors of hell. Nobody is ever prepared. And once it does happen, it’s too late to take care of a lot of the practical matters they need to attend to.

I look my patients in the eye and tell them the truth.

“This happened to me. Here’s what you need to know.”

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox