Zika Could Cause Brain Damage Even in Infants Without Microcephaly

Even when there are no obvious signs of microcephaly, exposure to the Zika virus can still result in brain damage to infants, new research shows.

Microcephaly, a condition where a baby’s brain is underdeveloped and their head is noticeably smaller than normal, has been linked to Zika virus since October 2015, when Brazil was in the midst of a Zika-related public health crisis. Since then, infants exposed to Zika virus in utero but born without the telltale small head were hoped to have escaped the debilitating effects of the virus.

Zika damages neural stem cells

The new study found that, even when ultrasound showed no obvious signs of Zika damage, exposure to the virus caused neural stem cells to cease creating new neurons, the building blocks of the brain. And when neural stem cells exposed to Zika did create new neurons, some of the neurons were disorganized.

“Neurons normally have a symmetrical radial pattern, but when Zika has an effect on those new neurons, it messes them up; they have different shapes and have gaps between them,” says Branden Nelson, Ph.D., one of the study’s authors and a neuroscientist for Seattle Children’s. “The microcircuitry of that part of the brain is not going to work the same way.”

Because of these abnormalities, the affected area of the brain is unlikely to function properly, Nelson says—meaning that, down the road, a baby thought not to be affected by Zika could still develop abnormally, with signs not appearing until the child is a year or 2 years old.

This delay is due to two factors. First, assessing things like learning and memory is extremely difficult in infants, Nelson says. Second, the researchers found that neural stem cell changes were so subtle they were hard to spot during testing of the fetus, and could easily be missed during a standard pregnancy checkup because the changes can’t be detected via ultrasound.

“It seems to be incredibly hard to detect the damage from the Zika virus infection during pregnancy. Having a child with a normal size head at birth is not a clean bill of health,” says Kristina Adams Waldorf, M.D., co-author of the study and an obstetrician gynecologist who practices at UW Medical Center—Roosevelt.

Long-term damage?

The researchers are also concerned for what the neural stem cell abnormalities could do long-term once the babies become teenagers and adults. The new study cites other research that has shown a link between neural stem cell depletion and chronic conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia and depression.

“When the child is born they might seem normal but, because of certain events that occur during development, the child could manifest neurocognitive defects much later in life,” says Lakshmi Rajagopal, Ph.D., an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington and a scientist at Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

Recently, Zika was linked with an increase in birth defects in states affected by the virus; some of these cases involved microcephaly, while others did not. The researchers recommend that all fetuses exposed to Zika virus be monitored long-term after birth, regardless of head size.

How Zika spreads

Zika is part of a group of viruses known as flaviviruses, which includes West Nile virus, dengue fever and yellow fever. Flaviviruses are primarily transmitted via infected mosquitos or ticks, but Zika can also be passed from one person to another during sexual intercourse. New research also suggests that other flaviviruses, such as West Nile virus, could cause fetal damage during pregnancy.

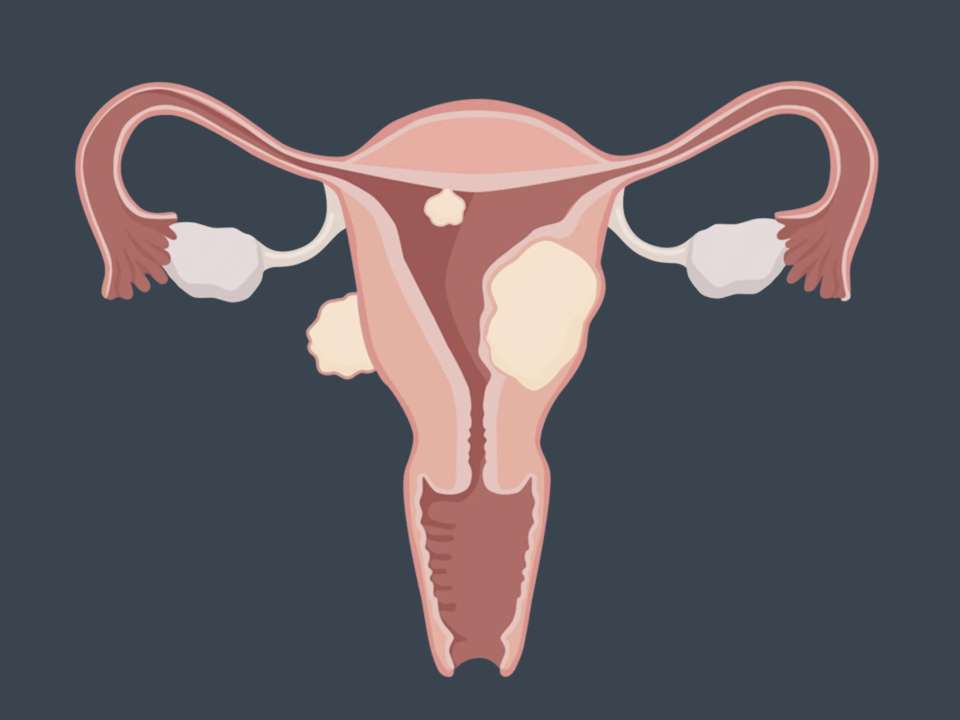

Exactly how long Zika can survive in an adult’s body is unknown—but could prove problematic. Unlike other flaviviruses, Zika likes to hide out in adults’ brains and reproductive organs, including the testicles, where the virus is protected from attack by the body’s immune system.

“Anybody who’s been exposed to Zika has the potential to have those parts of their body infected, and it might be a long-term infection,” says Michael Gale, Ph.D., co-author of the study and director of UW Medicine’s Center for Innate Immunity and Infectious Disease. “We’re just at the tip of the iceberg now in understanding that.”

A Zika vaccine

Most adults infected with Zika have mild symptoms, such as fever or rash, or are asymptomatic. However, Zika infection has been linked to an increase in adult cases of Guillain-Barré Syndrome, a rare but serious disease that causes the immune system to attack the nerves.

Luckily, Zika usually isn’t serious for adults—but researchers don’t yet understand why it can be so devastating for infants. There is currently no cure for Zika or treatment for infants affected by it. Adams Waldorf stressed that the best hope researchers have for fighting the virus is the development of a Zika vaccine. One such vaccine was recently fast-tracked by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and is currently being tested in patients. Not everyone will be vaccinated and scientists will need to develop other therapies to protect pregnant women, as well.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox