Uterine fibroids — non-cancerous muscular tumors in the uterus — are common: As many as 80% of women will have at least one fibroid by age 50; anyone with a uterus can get fibroids.

Fibroids are also treatable, and not just by hysterectomy, aka an operation in which the uterus is removed. Doctors have other options that are less invasive and preserve fertility.

Black women are at higher risk for getting fibroids and having more severe symptoms but are less likely to receive a full range of treatment options.

Why are Black women at higher risk for developing fibroids?

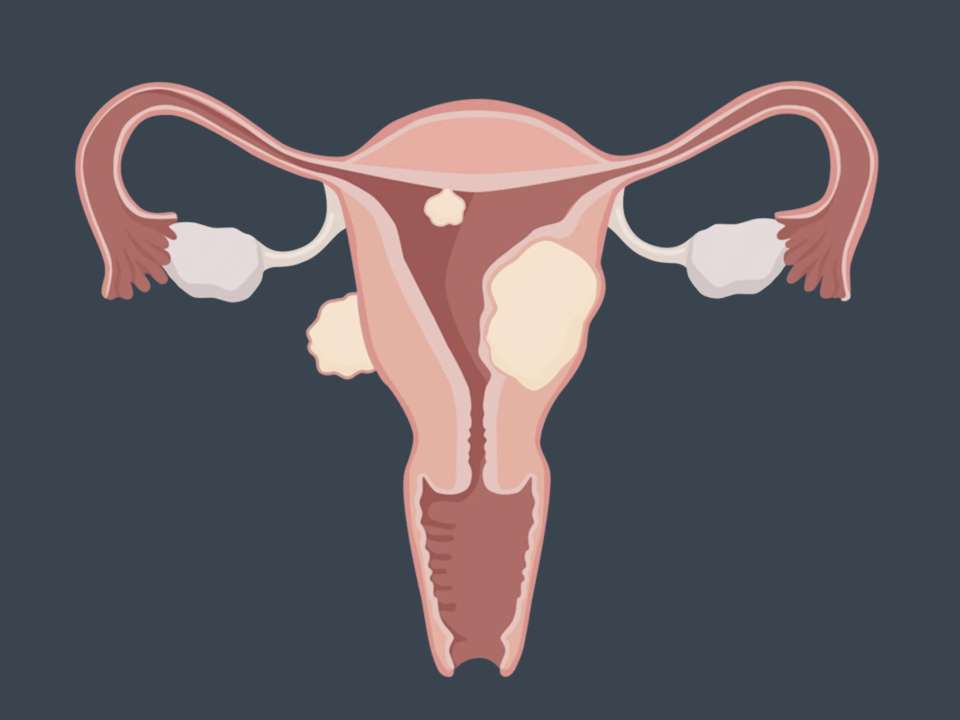

Fibroids are tumors made of muscle that can occur inside or on the outside of the uterus. Everything from environmental pollutants to genetics to physical inactivity may contribute to fibroid development. Many people who have fibroids don’t have symptoms, but among those who do, symptoms include pelvic pressure or pain, heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding, pain during sex, frequent urination or recurrent constipation. Fibroids can also cause fertility issues.

Research has shown that Black women are more likely to get fibroids in general and at younger ages. They also have a higher chance of developing more than one fibroid and having worse symptoms. The reasons for this disparity are complex and not fully understood.

“More research needs to focus on exposures that are experienced more frequently by Black individuals in the US related to systemic racism and sexism, which can help us understand the disproportionate impact of fibroids on Black individuals,” says Dr. Lisa Callegari, a UW School of Medicine associate professor of OB-GYN and core investigator at the Seattle-Denver Center of Innovation for Veteran Centered and Value Driven Care who practices at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

Some of these exposures include:

- Chronic stress from structural and interpersonal racism

- Environmental and occupational hazards like heavy metals, pollutants and endocrine-disrupting chemicals

- Psychological impacts like chronic stress from experiencing racism

- A higher likelihood of using harmful beauty products like hair straighteners or relaxers

Why do Black women face disparities in care for fibroids?

There are many reasons why Black women don’t always get the care they need for fibroids, but racism is at the core of most of them.

Access to care is often an issue. Additionally, doctors may not take Black women’s concerns seriously or may think they are exaggerating their symptoms — research has shown that, in all areas of medicine, Black people’s pain is often downplayed by medical professionals.

The Understanding Racial Inequities in Fibroid Care for Veterans (U-RISE) study led by Callegari and Jodie Katon at the VA Greater Los Angeles Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy also found that, among thousands of veterans who had symptomatic fibroids, Black women were less likely to receive any treatment — even when they had more serious complications like anemia.

In qualitative interviews, Black female veterans reported to the U-RISE researchers that they feared they would be perceived as trying to shirk their duties, were embarrassed by their symptoms and didn’t know how to explain them in a male-dominated environment, assumed their symptoms were normal, or were dismissed by doctors or only given one option for treatment.

Black women in the U.S. often distrust the healthcare system due to a long history of racial discrimination within the medical field. This can often make it hard for Black women to get the care they need.

The U-RISE study shows that when Black veterans had positive experiences, it was the result of having a regular doctor that they knew and trusted who communicated openly and answered their questions. The study also highlights that Black veterans felt empowered when they were able to advocate for themselves to get the treatment they wanted, working in collaboration with their doctor, says Shanise Owens, a PhD candidate in the UW Department of Health Systems & Population Health who helped lead the qualitative U-RISE study.

The disparity in fibroid care is a problem, not just because of the discomfort and debilitation that fibroids can cause, but because in rare cases, untreated fibroids that are symptomatic can lead to heavy bleeding that causes anemia and may even require a blood transfusion or emergency surgery.

Research has shown that when Black women do get treatment, they are more likely to have surgery, specifically invasive surgery, to treat fibroids and yet still have worse outcomes than women of other races.

“In general, our research emphasizes the necessity of culturally appropriate and race-conscious care, as well as the importance of shared decision-making when treating Black and other minoritized veterans with gynecologic conditions,” says Owens.

How can this disparity be corrected?

After interviewing 20 Black women who had symptomatic fibroids as part of the U-RISE study, Callegari, Owens and their colleagues determined several things that can be done by healthcare systems and leaders that will help move forward reproductive justice.

Cultivating patient-provider relationships that are grounded in trust is key. This means doctors and other medical professionals need training in how to provide race-conscious, culturally humble care. They also need to learn how to involve patients in decision-making and make sure they know all their options and have the information they need to make an informed decision.

“One key takeaway from our research is the importance of offering Black veterans multiple treatment options, including fertility-sparing choices,” says Owens.

Providing more support services to address the emotional and social aspects of having fibroids is also important, as is hiring more Black gynecologists, creating peer support communities and making sure patients have a way to share negative experiences with their healthcare system and have their concerns taken seriously.

“By taking proactive steps and embracing a patient-centered, culturally sensitive approach, healthcare institutions can work towards achieving equity in women's health services for all,” says Owens.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox