Plantar fasciitis is a common cause of foot pain. But did you know it might be more common in women? And that most of us will experience it at some point?

Here's how to manage it and prevent it from becoming a long-term problem.

Plantar fasciitis is more common than you think

More than 2 million people are treated for plantar fasciitis each year, according to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. It’s an equal-opportunity foot problem that doesn’t care how old you are, how active you are or what type of feet you have.

“Usually we can figure out why people get other foot conditions, but with plantar fasciitis, there isn’t always a pattern,” says Dr. Edward Blahous, a podiatrist and podiatric surgeon who sees patients at the UW Medicine Sports Medicine Clinic at Ballard.

It may be more common in women, who make up most of Blahous’ patients (though it could also be that women are more likely to go to the doctor for it).

People who have what Blahous calls a “tight Achilles tendon” may be more likely to get plantar fasciitis, as well as people who have flat feet, high arches or are obese.

“A lot of people who get it also have something wrong with their big toe joint, so there seems to be some correlation, though it’s not proven,” Blahous adds.

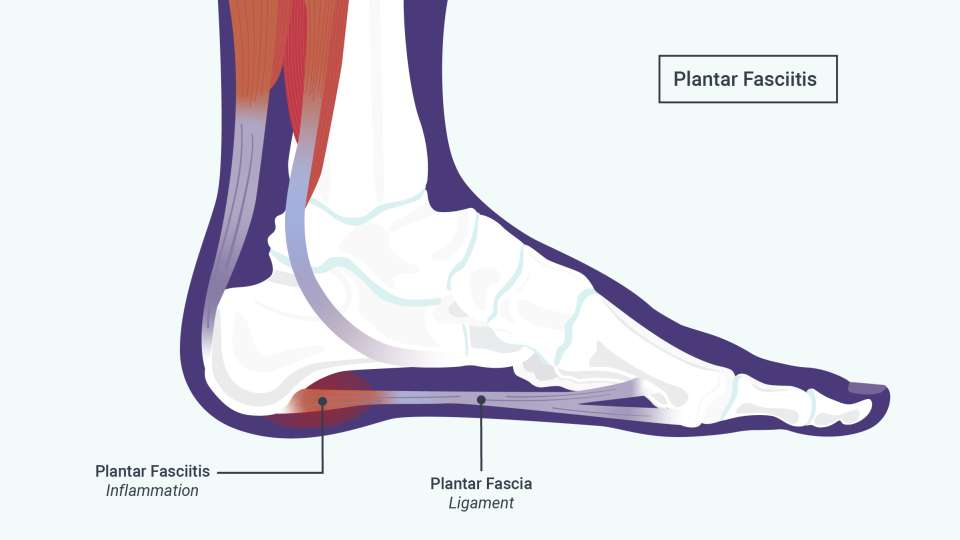

What plantar fasciitis pain feels like and why it hurts

Pain from plantar fasciitis can range in intensity from a minor nuisance to excruciating, Blahous says.

For many people, it feels like a stabbing pain on the bottom of their heel when they first step out of bed in the morning. The pain may worsen or come back if they’re on their feet for a long time.

The pain happens when the plantar fascia, a ligament on the bottom of your foot, is stressed and gets micro-tears. This causes inflammation and extra pulling on your foot bones.

How can I treat plantar fasciitis at home?

For people whose pain recently started and who haven’t had plantar fasciitis before, Blahous has a few different treatments to try:

- An over-the-counter arch support if someone has flat feet or a bunion

- Icing the heel

- Stretching the foot

- A night splint for the foot

- Anti-inflammatory medicines like ibuprofen.

Still, Blahous recommends going to the doctor as soon as possible, because not everyone’s pain responds to at-home remedies.

“Sometimes we do a treatment and it works, but sometimes it doesn’t and we have to try something else,” Blahous explains. “Plantar fasciitis is an individualized condition that benefits from customized treatment.”

If none of those things work, the next treatments to try are custom orthotics, physical therapy and cortisone shots, though Blahous only uses the latter in moderation and in certain circumstances.

“It’s tempting to use them more because they provide immediate gratification and pain relief, but repeated shots can lead to tissue tearing,” he says.

Another experimental therapy called platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections can be beneficial in some circumstances.

What happens if plantar fasciitis becomes chronic?

“We don’t really cure plantar fasciitis. If we live long enough, you’re probably going to get it, and it can be episodic. It can heal and then come back,” Blahous says.

Unfortunately, the pain can also last months, though this won’t happen to everyone.

If plantar fasciitis becomes chronic, the long-term inflammation usually fades but leaves behind a thicker ligament, which is why the pain persists. In this case, stimulating the ligament is a good idea, and anti-inflammatory treatments like cortisone shots and icing will only worsen the problem.

Blahous relies on low-energy shockwave therapy for people with chronic plantar fasciitis, which is designed to stimulate cellular activity and blood flow to your heel. He says it is so effective, he rarely needs to perform surgery and only relies on it as an absolute last resort.

So yes, some people do end up needing surgery, but most of the time other treatments work.

Is there any way to prevent plantar fasciitis?

Let’s start with the not-so-great news: Since doctors don’t know exactly what causes plantar fasciitis, there isn’t a specific way to prevent it.

But the good news is there are things you can do to reduce your chances of getting it.

Reducing the number of inflammatory foods you eat, and losing weight if needed and possible, can be helpful, Blahous says.

Wearing shoes around the house and supportive shoes when walking and exercising — even if you’ve never had heel pain before — is also important.

Take that as all the justification you need to go shoe shopping.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox