For some, it starts with a cough, a fever and difficulty breathing. For others, it begins with a dulled sense of taste and smell. And for a yet untold number of people, it’s marked by nothing at all.

You might get so sick from it that you need to be hospitalized and placed on a ventilator. You might just think you have a regular cold. Or you may not even know you have it in the first place.

These are the mysteries of COVID-19, the disease that’s become a global pandemic and has sent medical experts racing to uncover its secrets.

In the span of about four months, scientists have sequenced the genomic code of the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes the disease and learned how the virus affects your body. Still, there are a lot of unknowns, like why some people are affected so differently than others.

To help shed light on why that is and where the world is in the fight against COVID-19, Dr. Paul Pottinger, director of the Infectious Disease and Tropical Medicine Clinic at UW Medical Center – Montlake, and Dr. J. Randall Curtis, a critical care physician specializing in respiratory diseases at Harborview Medical Center, explain what we know so far and what we have left to discover.

A new and different coronavirus

If you’ve heard this particular virus described as “new” or “novel,” that’s because it’s not the only coronavirus out there. Coronaviruses are actually a family of viruses, all known for their spike-studded exteriors.

There are four main genera of coronaviruses, each distinguished by differences in the virus’ structure: alpha, beta, delta and gamma. Alpha and beta coronaviruses infect humans and other mammals, while delta and gamma ones mostly affect birds.

Some coronaviruses just cause a common cold, but others have made headlines before. Two well-known examples include MERS-CoV, which has caused infections in the Middle East, and SARS-CoV, which caused the SARS outbreak of 2003. This new virus is responsible for the current COVID-19 pandemic and is much better adapted to the human body than its predecessors, resulting in many more overall cases.

“Like the other coronaviruses, it infects the body through the respiratory system and may cause a generalized inflammatory reaction, such as fever, muscle aches, cough and shortness of breath,” Pottinger explains. “The main concern with COVID-19, however, is that some people do very poorly with this infection and can have a complicated or even life-threatening course.”

A respiratory system under attack

COVID-19 spreads in two main ways: directly from person to person, when an infected individual coughs or sneezes close to someone else, or indirectly, when a healthy person touches an infected surface and then touches their eyes, nose or mouth.

Like its cousins SARS and MERS, COVID-19 is a viral respiratory illness, meaning it affects the parts of your body that you use to breathe. This is why you may experience symptoms like a cough or shortness of breath.

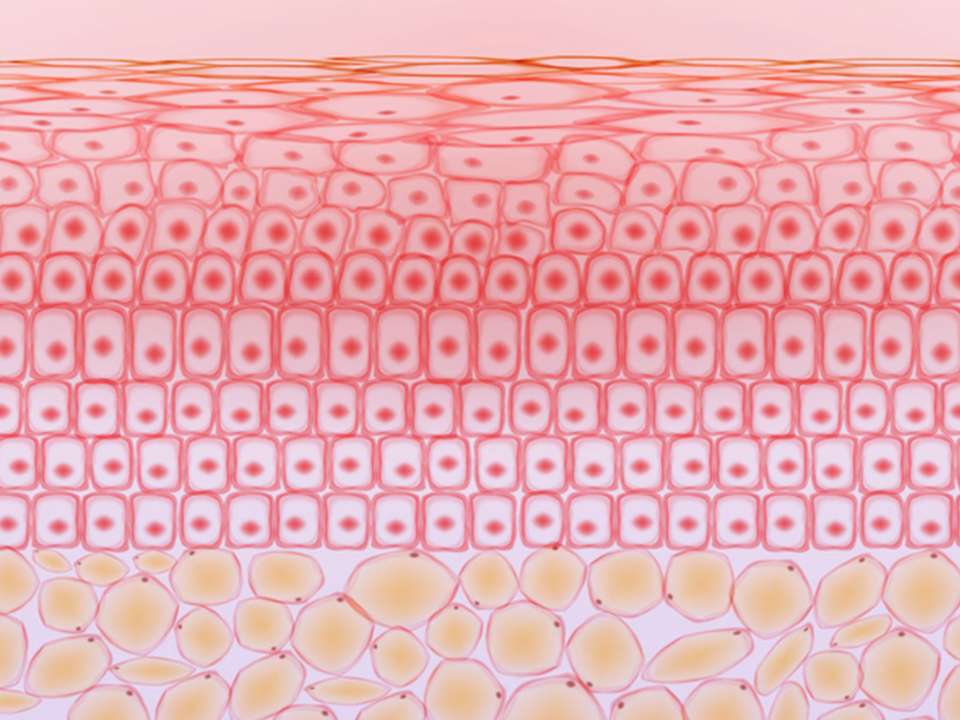

“Once the virus enters your body through your respiratory system, it begins to invade the cells that line your airway,” Pottinger explains. “The virus attacks the nose and mouth, down to the back of the throat, the trachea and the lungs themselves.”

Remember how coronaviruses have those characteristic spikes? These allow them to attach to healthy cells in your body. Once the coronavirus gets into your body and hooks onto a cell, the virus injects it with genetic material called RNA. This genetic material overrides your cell’s normal functions and instead forces it to produce more copies of the virus.

In essence, the virus hijacks your healthy cells and turns them into its minions in order to replicate more virus.

A viral load conundrum

Usually your body can heal itself by making new healthy cells and ramping up an immune response to destroy any infected one. But there are other factors at play that can allow the coronavirus to gain an upper hand, which explains why you may respond very differently to the virus than someone else.

One is how healthy you are before becoming infected.

“For people living with chronic lung disease or disease of the upper airway, especially people who smoke cigarettes or use vaping products, the immune and repair system is dramatically impaired,” Pottinger says.

Another factor is something called the viral load, a measurement of how much of the virus is in your body. This indicates how well the virus is replicating. For some diseases, the higher the viral load — aka the faster the virus is able to make copies of itself — the more serious the resulting illness.

In the case of the SARS outbreak from 2003, a patient’s chances of developing a severe illness instead of a mild one may have depended, in part, on that person’s particular immune response and overall health.

A “just right” immune response

The other factor in how well or how poorly your body is able to fight off the coronavirus is your body’s immune response and your unique genetic makeup.

Pottinger compares it to the classic children’s story “Goldilocks and the Three Bears.”

“In some cases the immune response is too much, and in some cases it’s too little,” he says. “Then there are some people who have just the right amount of immunity that develops in the right amount of time so that they only have mild symptoms.”

When your immune response isn’t robust enough, your body can fall behind on destroying infected cells and the virus can spread out of control. When it’s too forceful, an occurrence that’s called a cytokine storm, your body can release the wrong amount or an imbalance of inflammatory chemicals and end up attacking your body instead.

Here’s how it works: When your cells become infected, they cry out for help from your immune system. That help comes in the form of killer T-cells, which release chemicals called cytotoxins to destroy infected cells and prevent the virus from spreading.

While cytotoxins are necessary to help your body get the virus under control, they also leave an aftermath of symptoms like muscle aches, headaches, fatigue and inflammation-induced digestive issues like diarrhea.

This unique-to-you immune response may explain why you can get different symptoms from COVID-19 than your neighbor or friend.

An organ damage mystery

Although the lungs and airways are the most common targets of the disease, there are also some people who also experience damage to the heart, kidneys, liver or gastrointestinal tract.

In one paper summarizing findings of 26 people who died from COVID-19 — all due to respiratory failure — nine patients were found to have serious kidney damage due to the infection.

It might be that the virus has the ability to spread to other parts of the body. Or it could be because of an inappropriate immune response that ends up doing more harm than good. Researchers are still working to find out more.

“We have much to learn about why the virus has such a dramatically different effect in some patients compared to others,” says Curtis, the critical care physician who specializes in respiratory diseases. “It seems likely that some of this variability in response is due to underlying genetic differences, but we don’t understand these differences yet.”

A still-unknown path to recovery

Most cases of COVID-19 can be treated at home while your body’s immune response ramps up and fends off the viral attack. But in rare instances, you may need to go to the hospital if your illness becomes too severe.

“There are no proven treatments for COVID-19, but a number are being considered,” Pottinger says. “Whether any of these treatments is beneficial, either alone or in combinations, remains to be seen.”

COVID-19 can cause severe pneumonia that can make it difficult to breathe. As a result, many hospitalized patients require supplemental oxygen delivered by nasal prongs in the nose or by a face mask.

In the most extreme cases, when your lungs are so injured that you’re unable to breathe on your own, hospital staff will turn to ventilators. These machines, connected to a tube down the throat, can help patients with injured lungs get the oxygen their bodies need as well as get rid of the carbon dioxide that builds up.

“Ventilators allow us to give very high levels of oxygen, and the ventilator machine can take over the work of breathing when it becomes too much for the person to be able to do on their own,” Curtis explains. “With COVID-19, we are finding that patients may require ventilators longer than most types of pneumonia, often for two to three weeks or more.”

Once your immune system gets the virus under control, your body will begin its natural healing and repair process. New cells will replace damaged or destroyed ones, and you’ll eventually return to your normal state of health.

“This process takes time,” Pottinger notes. “People getting better after COVID-19 may expect to feel extremely fatigued and not at their peak physical performance for weeks or perhaps longer after the virus is long dead and gone.”

An unpredictable future

While researchers have discovered a lot about the new coronavirus, there are still many questions that have yet to be answered.

Will the virus fade and disappear on its own like the coronavirus that caused SARS? Will it die down only to come back seasonally like the flu? Will researchers be able to develop a vaccine quickly enough to eradicate it or lessen its impact?

For now, it remains a mystery.

The info in this article is accurate as of the publishing date. While Right as Rain strives to keep our stories as current as possible, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve. It’s possible some things have changed since publication. We encourage you to stay informed by checking out your local health department resources, like Public Health Seattle King County or Washington State Department of Health.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox