No one wants to be that person. The one who is well-intentioned but ends up saying something offensive.

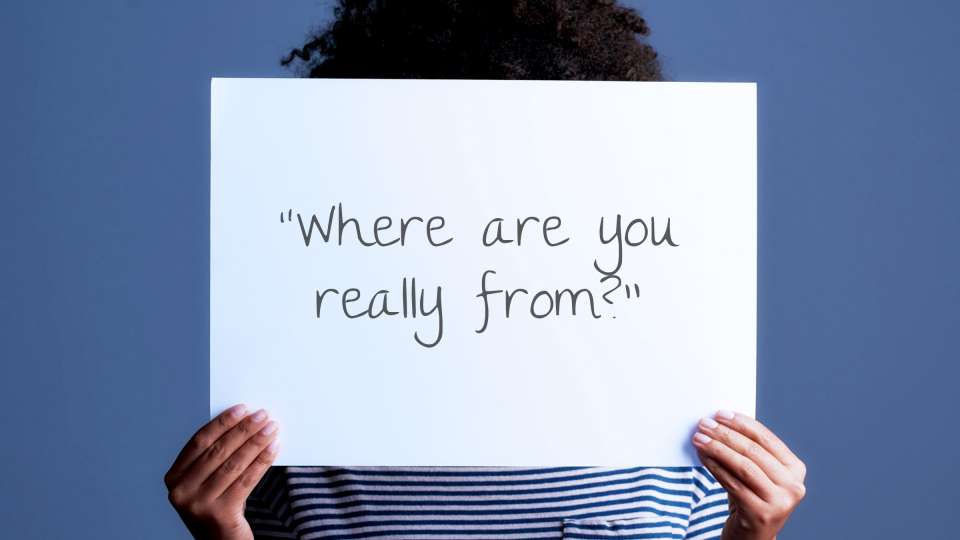

Maybe you asked a new coworker where they’re from — no, where they’re really from. Maybe you joked to a friend of color about them acting like a white person. Or maybe you asked your bisexual friend if she’s really bi because she’s dating a man.

The hard truth is that, while we don’t intend things like this to be offensive, most of us are capable of unknowingly committing these kinds of microaggressions that are harmful to people who are different from us in some way.

What are microaggressions?

Microaggressions are everyday insults, demeaning messages and indignities perpetrated by an often well-intentioned person in a dominant group against a person in a minority group.

The “everyday” part of the definition is important, because microaggressions aren’t the same as overt racism, homophobia or other bias. They aren’t intended to cause harm and the person perpetuating them probably has no idea they just said something offensive. What makes microaggressions offensive isn’t the exact words or actions but instead the underlying meaning that reveals bias.

Take the example mentioned above asking a coworker where they’re really from. You might think you’re just showing interest in their life by asking a common question. But to them, your insistence on not believing their first answer shows that you made an assumption about their homeland based on their appearance; maybe that because their skin is dark they can’t be “from” the United States.

That’s because of intersectionality, a concept that recognizes how all of our intersecting identities — like race, gender, sexuality, class and more — interact. Each of us has a unique intersection of identities, which means we all have the capacity to believe harmful stereotypes about people who have different lived experiences than we do.

Jonathan Kanter, a clinical psychologist and director of the Center for the Science of Social Connection at the University of Washington, uses an iceberg analogy to explain how microaggressions fit into the bigger picture of prejudice. The tip of the iceberg is overt racism, sexism or homophobia, which is visible and unmistakable. Microaggressions are the harder-to-see biases that lurk under the surface, more common than overt racism but less detectable. The sea the iceberg floats in is the bias enabled by society and institutions.

While microaggressions aren’t intended to be mean or show bias, they are still harmful to the people who experience them — especially when someone experiences them regularly. And though microaggressions are rooted in biases we may not at first be aware of, it is possible to prevent ourselves from feeding those biases.

“I believe we can get better at this by slowing down during interactions and using what we’ve learned from social science to help us overcome obstacles,” Kanter says.

How microaggressions impact health

Before getting into why microaggressions happen and how to stop them, it’s important to note that this isn’t just about being kinder to people. That’s important, of course, but microaggressions have a bigger impact than that: They can actually interfere with someone’s health.

Many studies have shown that experiencing microaggressions has a negative impact on mental health as well as physical health. Adding to this problem is the fact that doctors, counselors and other care providers aren’t exempt from (unknowingly) perpetrating microaggressions against their patients, which erodes the patient-provider relationship and creates additional stress.

Some people counter this by claiming that people of color and other people who experience microaggressions are just being too sensitive. Kanter sees this as a microaggression in and of itself, noting a double standard in who we trust to accurately report their own health problems — and who we don’t.

“Psychology research is full of self-reports from white people, yet we don’t trust the same things from people of color,” he says.

Aside from considering the individual impact microaggressions can have on someone’s health, Kanter also stresses how important it is to look at the problem from a broader perspective as a public health issue.

How a “stuck” brain creates microaggressions

When you meet someone new, your brain begins a process called category activation, where it tries to fit the person into categories that have already been defined in your head — categories like the person’s race, gender, age and more.

If the person differs from you in any of those categories, your brain registers this. It’s an automatic process that happens instantly, so many people aren’t aware of it.

“The process is normal and we all engage in it; it only becomes problematic when we get stuck in it,” Kanter says.

The “getting stuck” means hyper-focusing on what makes that person different from you, instead of just noticing it and moving on. It often results in someone making a comment about that difference, which can come across as insensitive, especially if it’s the only thing the person is focused on.

If you get stuck on the difference, you might start feeling anxious about it, because you don’t understand it or you don’t want to say or do something to offend the other person by drawing attention to the difference. This is your amygdala, the brain’s fear response center, firing up. If you start feeling anxious enough, you might try to avoid the person or avoid the discomfort you feel.

Once category activation and fear team up, your brain is primed to go into stereotype mode. Even if you think you’re woke and won’t fall into the stereotype trap, your fearful brain is a different story: It is more prone to making assumptions about people based on the information it has absorbed from society, which reinforces harmful stereotypes about people from minority groups.

Tips to prevent microaggressions

Now that you understand what’s going on in your brain that creates a situation where microaggressions can occur, try these strategies to learn how to recognize and prevent them from happening.

Notice what you notice

When you see someone for the first time, take a second to list off in your head what you notice about them, especially their physical characteristics that are different from yours. Your brain is going to pick up on these differences instantly, so if you’re aware of that process you can prevent yourself from getting stuck in it.

You can practice noticing what you notice at home, too. Kanter suggests looking at pictures of all different people and paying attention to what your brain focuses on.

Question your beliefs

After you’ve paid attention to what you notice about people, ask yourself what beliefs you have that might influence what you notice. Why do you believe what you believe? What physical characteristics automatically trigger your brain to make an assumption about the person? If you’re more skeptical about the beliefs your brain jumps to about someone, you can prevent yourself from buying into stereotypes based on how someone looks.

Recognize the role of institutions and society

Remember Kanter’s iceberg analogy? Just like the glacier can’t exist without the sea, it’s impossible to thoroughly work to prevent microaggressions without recognizing how society, not just individuals, perpetuates them.

“It’s important to see how microaggressions interact with structural racism, because that’s where the root cause of harm is and where the most harm comes from,” Kanter says.

Think of just about any stereotype about a group of people; chances are, it’s not new, but instead has been around for generations. If you buy into stereotypes, you’re not believing in something that’s real: you’re subscribing to a belief system that was created long ago to justify unjust treatment of certain people.

It’s important also to learn how institutions were built around and benefit from suppressing people in minority groups. One example of this is the school-to-prison pipeline, where zero tolerances policies at public schools have made it more likely that black students, even those as young as preschoolers, will interact with the criminal justice system.

Don’t get fooled by colorblindness

The idea that someone can look beyond race because we’re all part of the human race — aka colorblindness — may seem like a tempting belief to subscribe to.

However, the colorblindness approach also refuses to recognize the dramatically different experiences people have because of race and racism, and in doing so negates those experiences.

Plus, colorblindness simply doesn’t work in reality.

“Whatever our brains try to suppress is much less likely to successfully be suppressed,” Kanter says.

Believe people

People who are part of majority groups can usually go through the day without being reminded of that; for example, a white person can spend the day at work not having to think about the fact that they’re white and how others might perceive them because of it.

For many people in minority groups, this simply isn’t the case. They are constantly reminded of the aspect of their identity that makes them “different” because of the way others treat them and act around them.

It can sometimes be difficult for white people and others from a majority group to recognize this because they haven’t lived it. But it’s important to believe that people are telling the truth when it comes to what they experience — even if that means leaning in to the scary realization that what they have to deal with is worse than you thought.

“It’s uncomfortable, but you have the privilege and safety of getting to choose to think about this on your own time and in your own environment. People who actually have to experience it don’t get that choice,” Kanter says.

Lean in to empathy

Most of us want to be kind to others and show that we care, but that might seem harder to do when you don’t personally relate to what someone else is going through. This is where empathy comes in. You may not know exactly how the other person feels, but you can put yourself in their shoes to understand where they’re coming from.

There are many nuances to being empathetic. You have to be a good listener, and really hear what someone tells you. You have to be willing to go there with them and to believe them. You have to recognize that, no matter how different your own truth is, what they’re going through is true for them. You have to be vulnerable.

Ultimately, being empathetic is just about being a good friend.

“Validate that they’re sharing something with you that’s difficult. You can’t fix it, and they know that. They’re looking for bonding and support, not a solution,” Kanter says.

Decide how to be your best self

Kanter recommends coming up with a list of things you can do (and not do) that will get you closer to being the best version of yourself. He calls the list of things you can do “toward” behaviors, and the list of things you shouldn’t do “away” behaviors; the toward behaviors help you move toward your best self, and your away behaviors, well, don’t.

After you make your list, find ways to practice your towards behaviors and avoid your away ones.

Try not to get defensive

If someone feels threatened in any way, the default reaction is to defend themselves. This applies even when the danger isn’t literal, but rather a perceived attack on identity or someone’s value as a person — like when someone calls you out for saying something insensitive.

You may try to defend yourself by saying you didn’t mean it, that you didn’t know you were doing something wrong. And that may be true. But it doesn’t change the way your words or actions impacted someone else.

Instead of getting defensive, try to take a moment to calm down and recognize that it probably took courage for the other person to bring this up to you. They aren’t attacking your self-worth, they just want you to understand why the thing you did is hurtful.

“When people call you out, they’re pointing these other processes out and showing you the bigger picture, not saying you’re lying or expecting you to say you’re a bad person,” Kanter says.

Practice by putting it all together

Kanter encourages people to try a short exercise that will help them learn to get comfortable with being uncomfortable; that is, to be ready and willing to confront their beliefs, pay attention to the assumptions they make, practice being less defensive and more empathetic, and be ready to be a good listener. It’s an exercise you can try at home to lower your natural defenses and be more aware of your actions.

Start by imagining you’re going to have a conversation with someone who is different from you. Maybe this person is someone you already know, or not. Notice if you feel any tension in your body and focus your attention on your breath, breathing evenly and at a natural pace. Then focus on your thoughts and allow yourself to lean into the experience: tell yourself to truly listen and really hear what the person tells you. Promise yourself that you will show empathy when you respond to the person.

By doing these things, you’ll be in a better place to respond well when you notice your brain making assumptions, when someone calls you out, or when someone you know reaches out and wants to share their experience.

“The key to responding well is truly listening, expressing safety, validating what they say, and showing caring,” Kanter says.

If you find yourself feeling overwhelmed — after all, issues like systemic racism are huge and far-reaching — focus on the impact you can have on the people around you.

“The reality is that individual actions can go a long way to make change,” Kanter says.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox