What It’s Like to Live With an Invisible Illness Called POTS

Like many 20-somethings, Jocelyn Willey couldn’t wait to see Taylor Swift in concert. But unlike her fellow concertgoers, Willey attended the pop star’s show in pain, right after visiting her doctor.

Neither of these things was out of the ordinary for her.

At the venue, she found her seat in row 19, close to the stage. While she sat waiting, someone looking for their seat squeezed past her; though not forceful, Willey’s attempt to make room was enough to dislocate her hip.

She knew she should go to the emergency department. But she couldn’t miss the concert. So she stayed, pain tempered by her excitement to see one of her idols.

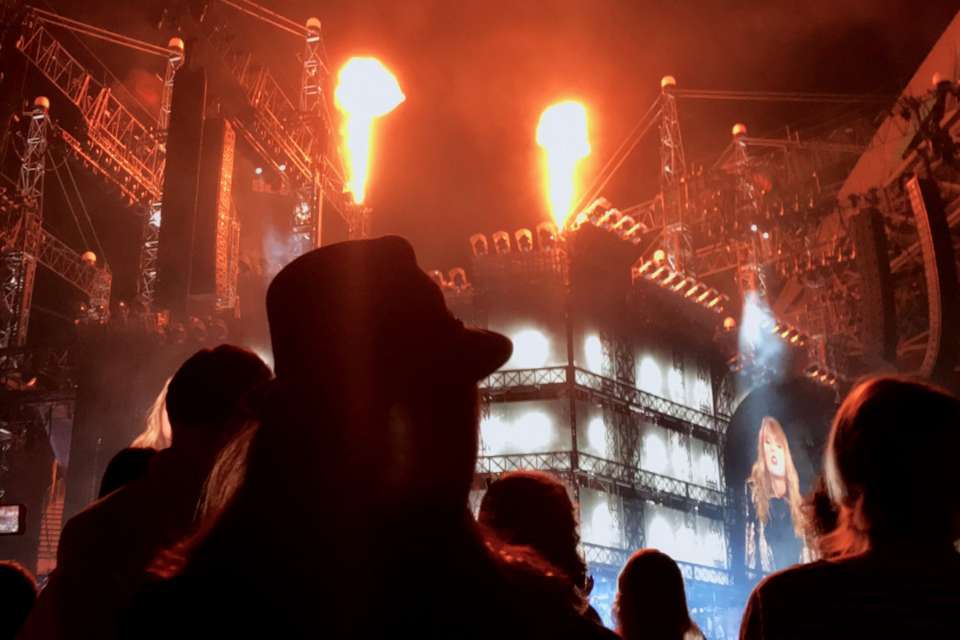

But soon her joy turned to discomfort. Everyone around her stood when the concert started, and kept standing as it continued. Willey couldn’t stand — not for long periods of time, anyway. Not because of her hip, which certainly ached, but because of a condition she has called postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or POTS.

POTS is a type of orthostatic intolerance, an inability of the body to regulate blood pressure upon standing. If someone with POTS stands after sitting or lying down, their heart will start beating rapidly. Some people faint.

Since POTS meant Willey couldn’t stand throughout the show and couldn’t keep changing her posture from standing to sitting, she was forced to watch on the giant video screens hung around the stage.

“It made me realize how different I am from everyone else,” she says. “I wouldn’t talk about it or look at posts [on social media] about the concert for weeks.”

Willey has other medical conditions that make dealing with POTS even harder. She was born with a rare illness called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, where inhibited collagen production in the body leads to weak connective tissue. People with EDS dislocate joints regularly, bruise easily and have chronic pain.

Despite this, Willey doesn’t see EDS as her most debilitating condition.

“POTS debilitates me the most. I’ve never had surgery for it, I don’t take a lot of meds for it, but it stops me from going grocery shopping or hanging out with friends. The tiniest things trigger me,” she says.

Tiny things, like standing during a concert, that many take for granted.

One piece of a puzzle

The term POTS is used to describe a wide range of symptoms that often co-occur, rather than a defined set of symptoms that occur in every single patient with the syndrome. Symptoms include things like widespread bodily fatigue, brain fog, chronic pain, headaches, anxiety and stomach problems, and can affect the entire body.

If navigating these symptoms is somewhat nebulous for patients, diagnosing the disease is equally as mystifying for doctors.

Symptoms can vary from person to person, multiple disease mechanisms have been proposed and often a specific cause cannot be identified. The syndrome has been linked to everything from platelet disorders to the HPV vaccine. The truth is, no one knows what exactly leads to POTS — and it’s likely more than one thing, says John Oakley, M.D., Ph.D., a neurologist who practices at both Harborview Medical Center and University of Washington Medical Center.

Traditionally an expert in epilepsy, he has become somewhat of a go-to doctor for local patients with POTS, thanks in part to helping treat Willey.

Willey became Oakley’s patient in 2016, about three years after she started getting POTS symptoms.

“He hadn’t treated many POTS patients before, but my case interested him. I have three- to four-hour appointments with him. He comes in on his days off, tries different meds, asks detailed questions,” Willey says.

She says she likes being able to help her doctors learn about POTS. While many patients may expect doctors to have all the answers, Willey doesn’t. She knows better.

In 2015, the mystery of POTS almost cost Willey her life. During hip surgery, she began bleeding much more than doctors anticipated.

“I almost bled out and needed 5 units of blood and fresh frozen plasma and an emergent procedure to put metal coils in my iliac artery because the bleeding wouldn’t stop,” she says.

She says her doctors think this rapid bleeding was due to POTS. Some research shows that the blood vessels of POTS patients behave abnormally, constricting and loosening in unpredictable ways.

Now that her doctors are aware, they can be extra cautious. But, until POTS is better understood, other patients could face similar danger.

The dysfunction of functional diseases

POTS being little-understood in the medical community and its variance among different patients mean it is also often misdiagnosed. When it is diagnosed correctly — sometimes years after symptoms first appear — doctors may find that they’re forced to treat the symptoms rather than the cause.

“These are challenging symptoms to try to diagnose. They often don’t have a structural cause we can see, we can’t biopsy it or take pictures of it, can’t get a bloodwork panel that demonstrates the symptoms. Think of it as a problem with the functioning of the system. Medicine doesn’t know how to deal with that very well,” Oakley says.

Functional diseases and disorders mean that there aren’t any visible problems in the body — no injuries, tumors or inflammation. Everything looks healthy, but it doesn’t function that way.

Doctors think POTS symptoms stem from an impairment in the nervous system, specifically in the way the autonomic nervous system (ANS) signals to various parts of the body. The ANS is responsible for our fight-or-flight response, things like heart rate and digestion, and reflexes such as sneezing and swallowing.

But why does the ANS start functioning oddly? Research shows that POTS often occurs after a major illness or infection, or even after pregnancy. Still, that doesn’t explain why POTS begins, or why it can be so severe when nothing looks physically wrong with the body.

“It doesn’t mean that the ANS is structurally broken, either,” says Oakley. “Sometimes it may be the ANS is acting appropriately to compensate for other problems, and some symptoms are part of that compensation.”

The hysteria problem

One thing doctors do know for sure? POTS affects way more women than men — approximately a 5-to-1 ratio. And since an estimated million or more people live with POTS, that’s a lot of women who suffer from a condition no one fully understands.

Because of this, many women who have POTS find themselves fighting not only a host of confusing symptoms, but also a medical culture that dismisses or discredits their experiences.

It doesn’t help that many POTS patients are young women who look healthy. It’s easy for other people, even doctors, to write off their symptoms as anxiety, even though research contradicts that assumption.

Willey relates to this. She has been treated for anxiety unsuccessfully, largely because she doesn’t believe she actually has an anxiety disorder. She sometimes gets physical symptoms of anxiety but can’t identify any specific reason for feeling anxious.

While it’s important to recognize that anxiety can play a role in POTS, it’s equally important not to dismiss POTS as a condition caused by anxiety, Oakley says. Doing so not only risks missing important insights into the syndrome but also stereotyping people who have it.

“POTS is in a group of conditions that are heavily weighted toward women and have been known about for hundreds of years. They’ve been called various things, like hysteria, and largely ignored in terms of their mechanisms and in understanding a good approach to managing symptoms,” he says.

A difficult diagnosis

Until 10 or so years ago, Oakley hadn’t heard of POTS. He was tasked with creating a dynamic way to test ANS function. After developing a test, he noticed a dramatic increase in the number of patients requesting it.

Currently, an average of three patients each day take the test. Some of these people end up being diagnosed with POTS.

It involves taking an electrocardiogram (EKG) of a patient’s heart to determine heart rate, while at the same time monitoring their blood pressure and how much they sweat. Then the patient does things like deep breathing or breathing through a tube so doctors can monitor how their body responds.

Sometimes, other tests are needed for diagnosis. One is called a tilt table test and is what you would expect from the name: The patient is strapped to a table and their blood pressure and other vitals are monitored while the table is tilted, slowly. The nurse or doctor monitoring the patient’s vitals notes how they change in response to the tilting.

Even with these tests, diagnosis is tricky, Oakley says, because of how variable POTS symptoms are.

It took around five years for Willey to get a correct diagnosis for POTS; her symptoms began in 2013. It took six years for her to get approved for disability, due to POTS as well as her other conditions like EDS.

The trouble of treatment

Treatment is equally as complicated as diagnosis. No clinical trials have attempted to find a conclusive cure for POTS, and few doctors think such a thing is possible. Instead, doctors draw on findings from individual studies on how best to treat different POTS symptoms, Oakley says.

“What we’d like to do is re-examine the categories that we’re using to diagnose people. POTS is probably made up of groups of people who experience different things and have different underlying causes. With well-defined groups, it would be easier to learn how people respond to different treatment strategies,” he says.

At Oakley’s instruction, Willey was recently outfitted with a peripherally inserted central catheter, or PICC line, that delivers fluids directly into her body.

Experimental studies have shown that IV fluids can ease POTS symptoms, and that seems to be the case for Willey. She says she quickly noticed improvements in her symptoms after starting IV fluids. In January 2019, she had surgery to hopefully prevent her hip from dislocating so often. (Doctors were prepared this time in case she began bleeding abnormally again, but she didn’t.) At that time, she also had her PICC line installed.

Since then, she’s run into complications. Things seemed good at first: her hip was healing well, her POTS symptoms eased thanks to the PICC line. But then she caught an infection and went to the hospital — a decision that saved her life, since doctors discovered she had sepsis.

Her PICC line had to be reinstalled, but the new one is causing the artery it’s in to become inflamed — a consequence of having EDS, Willey says. She could have the PICC line removed, but so far it’s the only treatment that has worked for her POTS symptoms.

Another option is to get a central line installed, which will deliver fluids into a large vein above her heart. It would likely provide greater relief, but any such procedure involves risks, especially for someone like Willey who has such a weak immune system.

A bright future for POTS patients?

Though there is no cure for POTS, many patients will feel better after making certain lifestyle changes, like taking in more fluids, eating more salt and doing physical therapy.

Willey is looking forward to a day, hopefully soon, when she can start doing the things she used to love. She wants to start working out again; she was active as a kid and enjoyed it. She’s thinking about going back to school (she had to leave when her POTS symptoms flared up). And she wants to go to the beach again, not just the moody coasts of the Pacific Northwest but the calm, clear, warm waters of distant shores.

But, more immediately, she’s looking forward to seeing Ariana Grande in concert. This time, she bought disability seats.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox