Wildfires Are the New PNW Summer Norm — and They’re Impacting Our Health

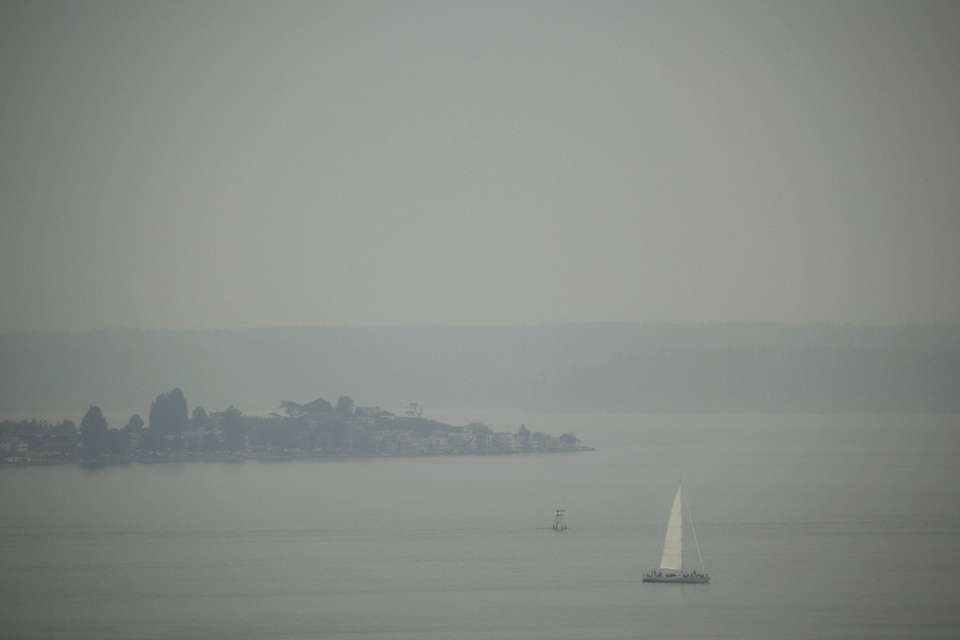

Warmer weather is here, and instead of feeling excited for the long sunny days and cool, sea breeze-tinted evenings that characterize Seattle’s best season, I’m dreading the inevitable: another summer of smoke.

The past two summers, I’ve been one of the many Pacific Northwesterners who has sighed in dismay upon seeing smoke blanket our region.

Though much of the smoke in the Seattle area comes from other places such as Canada, California and Montana, that could change in the near future. Scientists predict fires could become more common in Washington, including west of the Cascades.

The fires are an even bigger problem in the central and eastern parts of the state, where the climate is naturally hotter and drier. In a risk analysis commissioned by the United States Forest Service Pacific Northwest Regional Office, the most at-risk Washington cities are all in Central and Eastern Washington.

Fires, then, are a threat to all of us, no matter where we live. And in our ever-warming climate, they’re becoming more common. Are smoky summers our new norm? And, if so, what does that mean for our health?

Why wildfires happen

Wildfires have been increasing nationwide for decades, according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment published last year by the U.S. Global Change Research Program.

In 2018, Washington state saw 1,732 wildfires burn 438,868 acres of land; 84% of these fires were human-caused, which is in line with the national average. While there wasn’t an increase in how many fires were started compared to previous years, there was an increase in how destructive they were.

Sometimes an action as simple as not putting out a match — or trying to plug a wasp nest — results in catastrophic and uncontrollable burning.

Human error alone wouldn’t be enough to drastically alter the makeup of wildfires, however. Climate warming also plays a big role by making wetter, colder seasons become hotter and drier, which leads to more availability of easily burned plants, says Brian Harvey, an ecologist and assistant professor at the University of Washington School of Environmental and Forest Sciences.

Harvey expects the trend will continue. While the forests of Eastern and Central Washington have adapted to, and can even thrive in, frequent fires — Ponderosa pines’ thick bark protects them from flames — the ecosystems in Western Washington are used to less-frequent fires, he says.

West of the Cascades, the abundant greenery spends years and years growing and thriving in our wetter, cooler climate, which makes it harder to ignite. Historically, when the right conditions occurred — warm, dry summers; ignition sources; and winds from the east — severe fires burned large swaths of Western Washington; this was normal for this area.

But a warmer climate and drier seasons could extend the window of time in which a fire can occur, meaning we could see an increase in fires throughout the area. This could dramatically change the landscape and have a major impact on all of us who live here, Harvey says.

The problem of particulates

If wildfires continue affecting the western part of the state, we’ll also have to deal more frequently with the short- and long-term health effects.

Wildfire smoke contains particulates, tiny pieces of burnt plant material. Particles range in size, but ones that are 2.5 micrometers or smaller are the most dangerous because they can enter someone’s lungs and make their way into the person’s bloodstream and tissues, causing inflammation.

Chronic exposure to these particles is a known health risk, says Dr. Jeremy Hess, an emergency medicine doctor at Harborview Medical Center, who studies the public health impacts of climate change.

Particulates from burning trees and undergrowth is bad enough; worse is when human-made materials get caught in the flames, like what happened in California’s deadly Camp Fire.

“Those not only include biomass particulates but also other chemicals from homes, trash and all kinds of stuff. Those smoke plumes are even more dangerous because they have chemicals in them you don’t want to inhale,” Hess says.

The State of the Air 2019 report, commissioned by the American Lung Association, found that the Seattle-Tacoma area had the ninth worst amount of short-term particle pollution in the country between 2015 and 2017.

During this time, there were 11 “orange” days when the air quality was considered unhealthy for sensitive populations and four “red” days when the air quality was unhealthy for everyone. Orange and red are labels used in the Air Quality Index (AQI), a nationally used system for classifying air quality.

Since the State of the Air report only measured AQI through 2017, it doesn’t include data from the equally smoky (or perhaps smokier) wildfire season the region experienced last year.

Smoke signals for our health

This awful new state of reality shocked me — a Seattleite who had never experienced wildfire devastation firsthand — last summer when I spent half of August in Central Oregon.

Most of my trip occurred in a haze of smoke, more than I’d ever seen before. On some days, the smoke was so thick it blocked out the sun, making early afternoon look like early evening.

During that time, I felt ill. My head hurt, my sinuses felt swollen, my throat burned and my energy levels plummeted. One afternoon, my nose bled; outside, ash was falling from the sky like snow.

My symptoms are common for people exposed to wildfire smoke, says Dr. Cora Sack, a UW Medicine pulmonologist who treats respiratory disorders.

But even with my temporary discomfort, I didn’t have it half bad.

Many of Sack’s patients have lung conditions like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). For them, wildfire smoke isn’t just a temporary illness or inconvenience: It can be a life-threatening situation.

“They have a worsening cough or wheezing or have to use their inhalers more frequently when there’s more smoke. Some have had to get prednisone or other medications,” she says.

Some of her patients visit before wildfire season begins so she can help them create a coping plan. For one of her patients, who works outside, she writes doctor’s notes so he doesn’t have to work on smoky days.

Researchers know that for people who have existing medical conditions, wildfire smoke can trigger serious problems like stroke, a blood clot or a heart attack.

“When we look at it epidemiologically, we do see a clear relationship between these smoke events and emergency visits,” says Hess, who is also an associate professor in UW’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences.

How someone is affected depends on how strong the exposure is, how long it lasts and whether or not it recurs. Firefighters battling a woodland blaze are clearly more impacted than Seattleites taking a few smoky jogs around Green Lake. A Seattleite who has asthma is going to feel the smoke more than a Seattleite who doesn’t, even if their exposure time is the same. Children, pets and seniors are also at greater risk.

What exactly the long-term effects of wildfire smoke exposure are, researchers still don’t know. Sack compares wildfire smoke to a related problem that has been studied: air pollution. Research has clearly shown connections between high levels of pollution and diseases of the heart and lungs, she says. The particulates in wildfire smoke are different, though, and no one knows what they might be doing to us long-term.

“It’s definitely something we are concerned about and try to study and figure out what the consequences are, especially as wildfire seasons are becoming longer,” Sack says.

The social and mental toll of smoky summers

In Oregon, I felt better physically once I got back to clean air, but the experience haunts me still. I never saw flames, but I witnessed the leftovers of their destructive power: dead forests and walls of smoke.

Wildfires, like other natural disasters, can have a big impact on mental health, says Anjum Hajat, an epidemiologist with the UW School of Public Health. That’s because the danger they present is unpredictable, and they rob us of the sense of control we have over our lives.

Not everyone is impacted equally, says Hajat. She studies how people in underrepresented communities are typically the ones bearing a greater pollution burden and how that negatively impacts their health.

Though she doesn’t study wildfires directly, she recognizes a potential link between her work and studying the potential disproportionate impacts of wildfire-specific pollution.

“Environmental hazards are not equally distributed. People who are poor and in minority communities experience more air pollution. People with resources can get out of harm’s way, but other people cannot; it’s not an option for people living paycheck to paycheck, who need to keep working, or who have nowhere else to go,” she says.

Beyond contributing to physical health effects, Hajat has found in her research that air pollution can also potentially contribute to mental health problems. In a 2017 study of 6,000 people, she and her team found that people living in areas affected by more particulate matter experienced greater psychological distress than those in less-polluted areas.

“The depth of your loss from a fire affects the extent and duration of the impacts and health consequences you experience. Sometimes the losses cause depression and anxiety, sometimes they spill over into physical manifestations or exacerbations of chronic diseases,” Hess says.

Though people who lose homes, communities or even loved ones to the flames are clearly the most impacted, even those of us who aren’t in immediate danger can experience negative emotions related to the fires.

For Seattleites, there’s the stress of not having air conditioning or not being prepared for a dayslong stint indoors. There’s the concern when the smoke puts your family member with a medical condition at risk. And there’s the hard-to-quantify but very real existential stress of seeing the natural environment we love suffer.

“A lot of people value their outdoor experience here and feeling like they’re part of an intact environment; fire threatens that and makes it apparent our climate is changing,” Hess says.

Our future, up in flames?

For people hoping the smoky summers are an anomaly, Harvey offers an uncomfortable truth: they’re probably here to stay.

Wildfires have existed long before human development put us in their path, and they will continue to exist because the ingredients for them to occur will be here well into the future; plus, they’re a crucial part of many ecosystems, Harvey says.

He wants people to understand that, while fires can be a bad thing because of the danger they pose to us, fires are often a perfectly normal thing for the environment.

“We forget how much fire has played a fundamental role in sustaining and maintaining the natural beauty we know and love in this region,” Harvey says.

In the eastern part of the state, prescribed burns — where agencies like the Department of Natural Resources purposefully set controllable fires to fire-prone areas — could help clear undergrowth and saplings from overgrown forests and remove kindling that larger, uncontrollable fires could thrive on. Such burns have already begun.

In the western region, where prescribed burns aren’t beneficial, it’s important that we follow burn restrictions, do everything possible to prevent accidentally starting a fire and do our best to adapt to our changing region.

“We need to find ways for us as a society to best adapt and live with wildfire, accept the reality that it is a fundamental part of our region and mitigate the risk whenever and wherever we can,” Harvey says.

I recently visited an exhibit at Pacific Science Center called “Smoke Signals,” where a local artist felled burnt trees from Eastern Washington and shipped them into the city, placing them strategically around Seattle Center.

One of the trees stands by Pac Sci’s arches; at the right angle, you can see the Space Needle looming behind the blackened, stubby remains of the tree’s branches.

It’s a beautiful warning.

Tips for weathering the smoke

Since we're likely going to get smoky skies again this year, here are some tips from the experts for navigating fire season.

Keep an eye on smoke levels

Many websites (and even map apps) offer AQI monitoring so you can check how clean the air is in your area. If the AQI is between 101 and 150, that means the outdoor air is unhealthy to breathe for people in sensitive groups, like those with medical conditions. If the AQI is above 151, the air is unhealthy for everyone regardless of individual health.

Don’t exercise outside

Yes, we Pacific Northwesterners love going outside, especially in the summer. But if you want to do any strenuous activities, it’s best to stick to the gym on smoky days. “Your first choice should be modifying activities. Going outside for a run with your N95 mask isn’t the thing you should do,” Sack says. (She’s seen people bike around the city wearing them, which she doesn’t recommend.)

Keep indoor air clean

If it’s smoky outside, keep your doors and windows shut. If it gets warm inside, use a fan, or if you have AC, set it to recirculate. With the lack of air-conditioned homes in this area, it can be difficult to stay indoors when your house or apartment feels like a sauna, but do your best to find alternate ways of cooling off.

If you must be outside, wear a mask

And not just any mask, but one that includes a filter that can actually keep particulates from entering your airways. The best option is what’s typically called an N95 mask. The Centers for Disease Control has a list of approved N95 masks.

Listen to your body

Sack wants to emphasize this, especially for people who may be at higher risk of developing symptoms from smoke exposure. If you’re outside and the smoke is bothering you, go inside. If you try to go for a run and your breathing feels different, head back home.

Use your car’s AC

Staying indoors is best, but if you must drive, use the AC exclusively because it will filter out particulates, whereas open windows (obviously) won’t.

Don’t be a fire-starter

Obey burn bans. With campfires and other outdoor fires, keep flammable items away from the flames and clear the area around the fire pit. Never leave a fire, even one in a small camp stove, unattended; keep water nearby at all times. When you put a fire out, do so thoroughly and with water to prevent any embers from reigniting. And pay attention to the wind: Windy weather can make an accidental fire spread and quickly grow out of control.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox