What to Say (and Not to Say) to Someone with Anxiety

It’s never not awkward telling someone I have anxiety disorders. And I’ve had to tell a lot of people: friends, family, supervisors, dates. (Nothing puts a damper on date night quite like saying, “Hey, so I’m really into you but I kind of feel like I’m going to die right now.”)

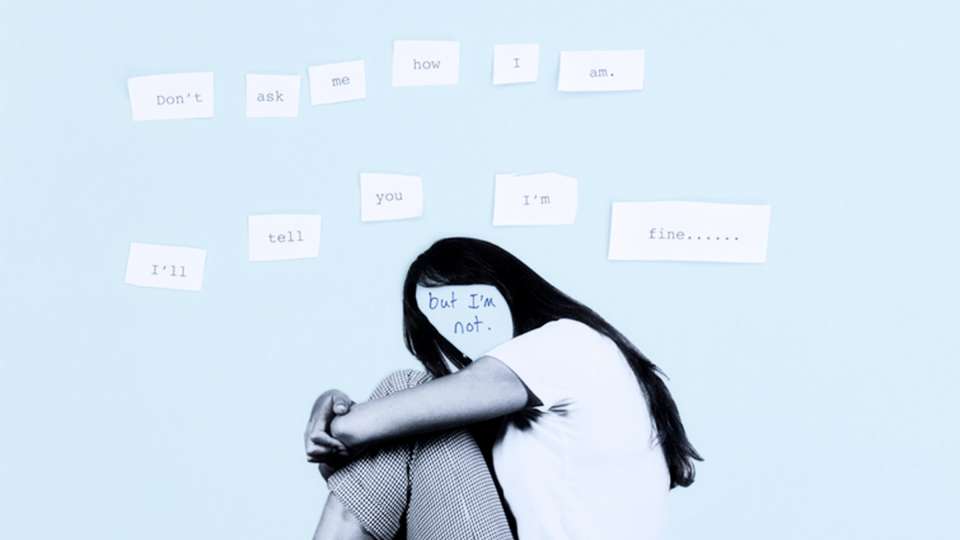

Opening up to others can be validating and freeing, but it’s always stressful at first because I don’t know how they’ll respond. Being stereotyped or treated insensitively when you’re struggling can be nerve-wracking, especially if you already get down on yourself for having anxiety. (Guilty.)

What I’ve learned in my many years of coming clean is that most people mean well. They don’t want to say the wrong thing, but it can be hard for them to know the right thing to say if they don’t know much about anxiety.

While everyone experiences anxiety, people experience differing degrees of severity, says Ty Lostutter, a clinical psychologist who specializes in anxiety and treats patients at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance at South Lake Union.

“Anxiety is normal and healthy. It keeps us safe and motivates us,” Lostutter says. “It only becomes a problem when someone becomes overly anxious and it interferes with daily life.”

Anxiety disorders are one of the most common types of mental illness — and they’re on the rise, no thanks to the pandemic. Around 19% of the U.S. adult population is affected in any given year. Chances are you know someone who has clinical levels of anxiety. With that in mind, here’s what to say and how to help someone with anxiety.

Don’t say: “I know what you mean. I had a panic attack when I saw Seattle rent prices.”

Panicking about the absurd cost of that tiny studio apartment makes sense because you need a roof over your head and can’t magically increase your salary. Panicking about taking a bus because you’re afraid of having a panic attack on said bus (true story) doesn’t.

There’s a difference between the uncomfortable but rational anxiety we all get in stressful situations and the sometimes debilitating but illogical anxiety super anxious people like me get in situations that aren’t actually stressful or threatening.

People with anxiety disorders experience anxiety over things others wouldn’t and with such intensity that it interferes with our ability to function and do things we enjoy. So unless you have a diagnosable anxiety disorder, comparing your anxiety to someone else’s isn’t helpful, and it can make us feel like you’re minimizing our experiences.

Instead say: “I’m always here for you.”

You don’t have to understand what your friend is going through to be there for them, and you don’t have to compare your experiences to theirs to show them that you understand what they feel.

If you don’t know what it’s like to have severe anxiety, be honest about that. But also let them know that you know it’s real for them and you want to be there to support them however you can.

Showing you care will help if your friend is self-conscious about their anxiety or has a hard time opening up about it. Listen without judgment to what they have to say and what their experiences are like. Being there for someone even when you can’t relate is a powerful way of showing support.

Don’t say: “Have you tried meditation/yoga/cutting caffeine/exercising more?”

Meditation and yoga and deep breathing and all of the other anti-anxiety trends that have taken pop culture by storm might be helpful for some people, maybe even your ultra-anxious friend. But they also might not.

Extreme anxiety can feel consuming, which means that small things like taking a few deep breaths might not be enough to counter panic in the moment. Anxiety can also make someone feel so restless that sitting quietly and letting their thoughts float away is pretty much impossible.

Everyone with anxiety has different relaxation techniques that work for them — and some people need to do something active, like go for a run, instead of sitting and breathing calmly. Others may need to work with a therapist. Don’t offer unsolicited advice unless you’ve been trained to treat people with anxiety disorders or you have one yourself and want to share your experience.

Instead say: “What can I do to help you?”

If your friend has been dealing with anxiety for a while, chances are they already know what does and doesn’t help them feel better. Ask what they need and then do it, even if their request seems silly to you. (Like that time I asked a friend if we could just not talk at all until I calmed down. Sorry, friend, but thanks for agreeing.) Showing you’re willing to offer assistance helps us anxious folk feel like we’re being taken seriously.

Don’t say (for the hundredth time): “Are you OK?!”

If your friend told you they’re feeling super anxious, they clearly are not OK. Constantly asking them for a status update can make them feel pressured to get better now. When we see someone we care about suffering, our instinct is often to try to fix it. But some things, including anxiety, can’t be fixed by outsiders.

Instead say: “Let’s go to a quieter place or go for a walk.”

If you want to try to help your friend get out of anxiety mode (and you know them well), you can try grounding them back in reality. Anxiety makes people hyper-focused on the thoughts, emotions and physical sensations that are causing the distress, so to get your friend’s mind off of those things, ask if they want to take a walk, listen to some music or go to a quiet corner.

Sometimes we need a supportive push to help break us out of our vicious cycle of panic and panicking about panic. Techniques like this are similar to what trained psychologists and therapists use as part of cognitive behavioral therapy, the gold standard of treatment for people who have anxiety disorders.

Don’t say: “Why aren’t you seeing a therapist/on medication?”

There’s nothing wrong with showing concern for a friend, but be careful it doesn’t come across as accusatory. Suggesting your friend should be doing something can create a sense of shame if they aren’t, or make them feel like they’re being judged. If they do need to see a mental health counselor or take medication, those are decisions they need to make on their own and at their own pace.

Instead say: “I’ve noticed you’ve been anxious a lot lately, and I’m concerned.”

If you notice your friend getting more and more anxious and you know they haven’t sought any kind of professional help, it’s OK to express your concern if it comes from the heart.

Instead of making it seem like they are the problem, focus on how their behavior is negatively affecting them and how you’ve seen anxiety change them: maybe they aren’t going to concerts anymore even though they used to love live music, or they haven’t been socializing as much and you’re worried about them being lonely.

If they’re open to getting help but feel overwhelmed, offer to do some research on good therapists or to wait for them in the lobby during their first appointment. Remind them that anxiety is treatable and that this isn’t something they have to fight alone.

The bottom line

If someone confides in you that they’re feeling anxious or having a panic attack, the most important thing to remember is that their feelings — and telling you about them — are a big deal. It takes trust to show that kind of vulnerability. Listen and respond in a way that doesn’t minimize their experience.

“You don’t want to shame them or not acknowledge they’re suffering,” Lostutter says. “You want them to feel like they’re being heard.”

There are definitely times when I haven’t been heard, when my anxiety has been dismissed or questioned, and those times haven’t been pleasant. But there have been even more times when I feel heard and validated — often by friends who don’t have an anxiety disorder. Knowing they care enough to listen and support me is all that matters, and it helps give me an extra boost of strength when I’m fighting off my symptoms.

Even if you can’t take your friend’s anxiety away, showing support can help them feel more comfortable and take away some of the stigma that compels them to hide — which is a pretty amazing thing to do for someone you care about.

This article was originally published on May 18, 2018. It has been reviewed and updated with new info.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox