He Sought Care for Schizophrenia. He Still Fell Through the Cracks.

On April 24, 2010, Zia Larson—a bright 21-year-old college student known for his wide grin and joyful demeanor—took his own life at Magnuson park in Seattle.

Larson’s mother, Verneta Seaton, knew her son was struggling with a recent schizophrenia diagnosis. But she wouldn’t find out until years later that the disorder ran in her family.

“No one in my family talked about it,” she says during an interview this past August. She heard relatives mention, in hushed tones, how her uncle “wasn’t quite right,” but never knew to make that connection to her son. One of Seaton’s cousins also has schizophrenia.

The disorder is known to have a genetic component, with research showing that gene mutations can determine inheritance. Additionally, a recent study identified a gene that could contribute by interfering with neuron connections. However, biology does not act alone: A variety of environmental factors, such as childhood trauma, teenage marijuana use and even season of birth, are linked with schizophrenia development in people who have a biological predisposition for the disorder.

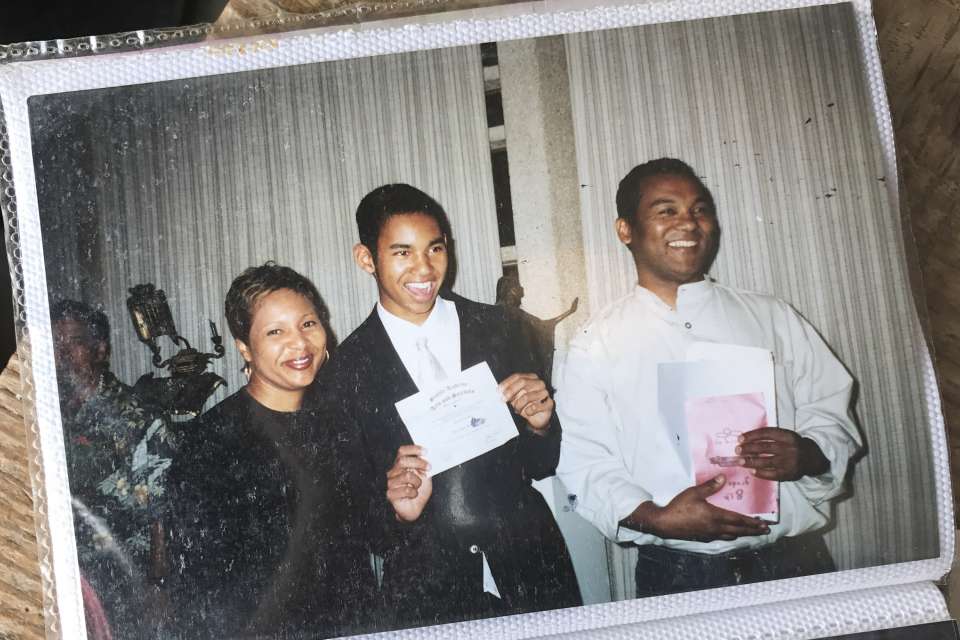

Halfway through the interview, Seaton retrieves a photo album from her bag and places it on the table. All the photographs are of Larson: swimming in a pool, at a birthday party, graduating from middle school. They chronicle his transformation into a young man, but his grin—wide, infectious—is the same in every image.

Except the last few. Seaton turns the pages and points out an older Larson, wearing glasses. These are the last photos she has of him.

“At the end there, you can see where he’s sick, his body language,” she says. The grin is indeed different, less natural, the look of someone uncomfortable in his own skin—posture “rigid,” as Seaton describes it.

She first noticed changes in Larson during his sophomore year of college at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. During a visit to Seattle, he reacted strongly when Seaton touched his foot affectionately, yelling and running into his room. He came out some time later, telling Seaton he hoped he hadn’t scared her.

Back at campus, his discomfort grew. He started calling campus security in the middle of the night, thinking one of his roommates had stolen from him. He developed an unhealthy relationship with food and, though he had always been slender, saw himself as fat, Seaton says.

“He talked to me about his paranoia,” Seaton says. “The way he was describing his body, the way he looked at food—it didn’t make any sense.”

Not making sense is both the reality and the stereotype of schizophrenia. The American Psychological Association describes it as being “characterized by incoherent or illogical thoughts, bizarre behavior and speech, and delusions or hallucinations.” Stereotypes take this a step further, labeling people violent or unintelligent.

Larson defies stereotypes. He was young and educated, sought help from a counselor on campus and was supported by his mom. He began taking medication, though he didn’t like the way it made him feel and would sometimes miss a dose, Seaton says.

“I think Zia’s spirit got discouraged. He didn’t have that maturity, I feel like, to know we could move past this. He was brave and was trying to confront it the best way he knew how,” Seaton says. “He didn’t challenge himself to keep going. He just needed to set himself free.”

A 2005 analysis found that suicide risk is highest shortly after illness onset, and that people with schizophrenia have a 4.9 percent lifetime risk of committing suicide, higher than the general population. They are also 3.5 times more likely to die prematurely, a recent study showed, often due to another chronic condition like cardiovascular disease.

Sometimes, a delay between symptom onset and seeking treatment leads to poorer outcomes and symptoms that are more severe—and that’s a problem, says Maria Monroe-DeVita, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist and Assistant Professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

“The problem is people have to fail in the system—or we fail them—and when they get sick enough we say they can finally qualify for this kind of program,” she says.

Schizophrenia onset typically occurs in someone’s teens or early 20s, but there are often signs before the illness fully manifests. This offers a critical opportunity to intervene before symptoms become disabling.

Monroe-DeVita is involved in the creation of an Early Psychosis Intervention Program at the forthcoming UW Medicine Behavioral Health Institute, which will be based at Harborview Medical Center. The program is designed so that clients will see a coordinated specialty care team comprised of a psychotherapist who can help to educate and teach wellness management skills, a psychiatrist who can prescribe medications if needed, a family therapist to educate and support family members, and a supported employment/education therapist who will help clients accomplish their personal goals, such as attending school or working.

“If we intervene sooner, we can potentially help them to get back on track with their lives more quickly. If we don’t and wait to help them later—how much have they lost by that point in their lives?” Monroe-DeVita says.

Despite the potential benefits of early intervention, there are also challenges. Losing touch with reality may not be a specific moment, but rather a gradual accumulation of thoughts and behaviors called the prodrome or prodromal phase. Symptoms during this phase—withdrawing from society, isolating oneself, mood and sleep changes—may not be alarming in and of themselves.

Determining psychosis risk is doubly complicated by the fact that prodromal symptoms are not uncharacteristic for teenagers. Sometimes, psychologists and families alike aren’t certain if a young person’s behavior is due to something serious like psychosis, or simply a teenager being a teenager, Monroe-DeVita says.

Because of this, education will be a critical component of the new UW Medicine program, Monroe-DeVita says; educating parents and families, of course, but also community members, mental health advocates and healthcare providers. Monroe-DeVita hopes to set up a consultation line providers could call if they are having trouble determining how best to help a patient.

Another potential barrier to treatment is stigma. If mental disorders are one large family, schizophrenia is the unloved stepchild. It is more stigmatized than other mental illnesses, even among psychiatrists. And while people with the disorder are responsible for only a small proportion of violence in society, media portrayals often depict them as violent and homicidal.

Seaton wants to see the conversation around mental illness change, and doesn’t want others to be silenced by the stigma that kept her from learning her family’s history.

“I’d like to see us treat our mentally ill with kindness and dignity, for people not to have to be ashamed to talk about when they have mental illness,” Seaton says. “Just like you’re not ashamed if you have heart disease or diabetes.”

To work toward this goal, Seaton created a foundation in Larson’s honor. Zia Larson’s Ray of Light Foundation held its first run/walk on September 13—Larson’s birthday—at Magnuson park. Some of the funds raised will go to the Early Psychosis Intervention Program.

As Seaton flips through the photo book, she sometimes cries, sometimes laughs, when mentioning her son’s accomplishments and quirks. She talks about Larson freely in her work as a flight attendant, and said her openness encourages strangers to share their stories and their families’ stories about schizophrenia. To her, this shows how schizophrenia can affect anyone—and that we as a society need to talk about it more.

“Zia’s my angel. He’s guiding me to do this. I could weep and whine and be in my own little pity party for the rest of my life, but I want to honor him through love,” Seaton says. “It was an honor being his mom.”

If you are feeling suicidal or know someone who is exhibiting warning signs of suicide, call 911 or the free National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1 (800) 273-8255. It is staffed 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Warning signs for suicide include:

- Talking about suicide or a wish to die

- Talking about feeling trapped, desperate, or needing to escape from an intolerable situation

- Feelings of being a burden to others

- Losing interest in things, or losing the ability to experience pleasure

- Becoming socially isolated and withdrawn

- Acting irritable or agitated

- Showing rage, or talking about seeking revenge for being victimized or rejected, whether or not the situations the person describes seem real

For more information, visit Forefront, the University of Washington’s suicide prevention program.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox