Let’s be honest: Most people don’t look forward to getting a Pap smear. It can be awkward and intimidating, not to mention a hassle to find time in your schedule. But it’s one of the most important things you can do for your health.

Pap smears are a key reason why cervical cancer is no longer a leading cause of cancer death among women in the United States. In recent years, however, the percentage of women who are overdue for their cervical cancer screening has increased.

Cervical cancer is nearly 100% preventable and can be treated if detected early. Yet, it remains one of the most common forms of cancer in women. The American Cancer Society estimates that in the U.S., 14,000 new cases are diagnosed annually and cervical cancer continues to kill approximately 4,000 women every year. Globally, that number is 342,000 per year, according to the World Health Organization, or around two people every minute.

(The statistics in this article refer to cisgender women because the sources they come from did not include trans or gender nonconforming people. We hope data for gender diverse people emerges soon.)

Dr. Linda Eckert, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the UW School of Medicine and author of "Enough: Because We Can Stop Cervical Cancer,” explains how we can all do a better job to prevent this disease.

What causes cervical cancer?

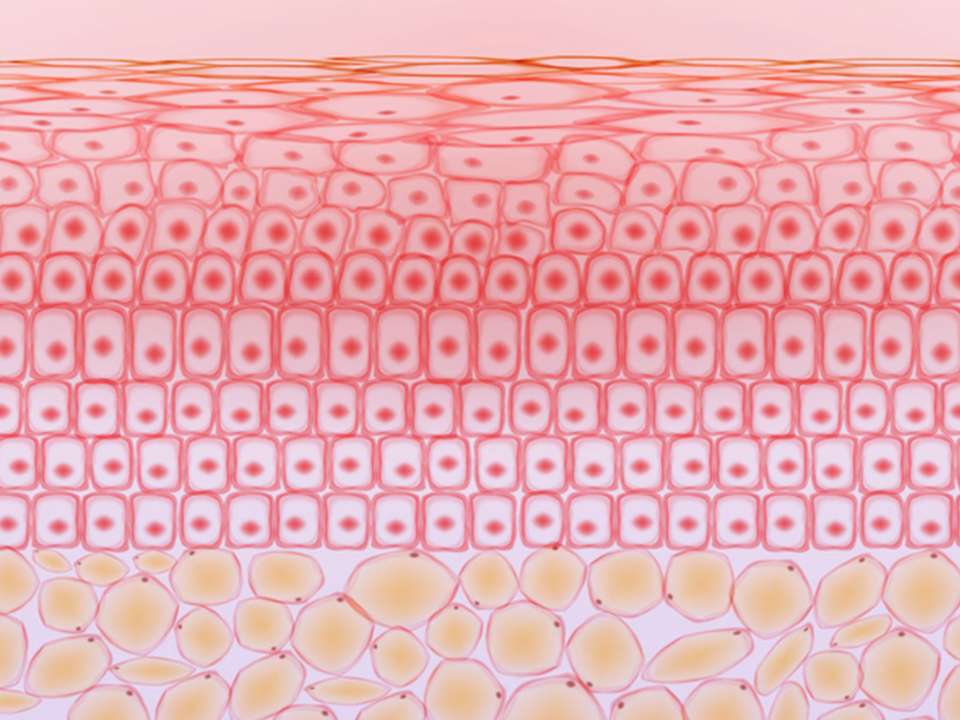

The cervix is the lower part of the uterus and connects the uterus to the vagina. Sometimes, cells that line the cervix begin to change. Over time, they can grow abnormally and spread, becoming cancerous.

Unlike most other cancers, doctors know its cause. Almost all cases start with a human papilloma virus, or HPV, infection, says Eckert. While there are many strains of HPV or human papillomavirus, roughly 70% of cervical cancer cases globally can be attributed to two high-risk types of the virus: HPV 16 and HPV 18.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection, and anyone can get it.

“By the time people have had three sexual partners, 50% will have an HPV infection. By the time people are adults, 80% will have had an HPV infection,” Eckert says. In other words, if you’re sexually active, there’s a good chance you may have had it.

The good news is that your body’s immune system usually clears the infection on its own. However, if you’re infected with a high-risk type of HPV and the infection persists for years, usually asymptomatically, it can affect the way cervical cells replicate, leading to precancerous changes in the tissue and potentially cancer.

Why is cervical cancer screening so important?

Cervical cancer can take years, sometimes decades, to develop, and symptoms usually don’t show up until the cancer has advanced or spread. That’s why routine screening is crucial: It can spot an HPV infection or precancerous cells in the cervix early on when treatment can keep cancer from developing.

“We have this lead time to detect changes at the level of the cervix before it becomes cancer,” Eckert says. “If you’re getting screened on a regular basis, it’s unlikely that there’s anything lurking.”

There are two main screening methods. The Pap smear or Pap test looks at cervical cells to see if there are precancerous or cancerous changes. There’s also the HPV test, which detects infections caused by a high-risk HPV linked to cervical cancer. Depending on your age and health history, your doctor may recommend one or both tests.

Why are so many people still getting cervical cancer?

While regular screening is key to preventing cervical cancer, following up with your doctor is just as important. “We have a real breakdown between screening and follow-up care. We’re losing a lot of people,” Eckert says. And it’s holding back progress toward eliminating cervical cancer.

She points to geographic location and socioeconomic factors as main barriers standing in the way. Procedures like biopsies or colposcopies, which examine the cervical tissue more closely, are expensive and people may not have insurance to cover it.

There isn’t equal access to providers either, especially those that serve low-income populations and rural areas. Cervical cancer disproportionately affects people of color. For instance, Black women are less likely to be screened, 30% more likely to develop cervical cancer and 60% more likely to die from it.

And because HPV is a sexually transmitted infection, there’s still a lot of stigma around it, which can keep people from getting the HPV vaccination and regular screening.

What can you do to prevent cervical cancer?

Here are three key things you can do to keep cervical cancer from developing.

Get the HPV vaccination

The HPV vaccine, which was approved in the United States in 2006, is an important tool to guard against cervical cancer. It protects against several high-risk HPV strains and prevents 90% of cervical cancers. The vaccine is safe and isn’t made from a live virus.

If you receive the vaccine before becoming sexually active and are exposed to HPV, it can prevent an HPV infection and greatly reduces the risk of developing cervical cancer.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine vaccination at age 11 or 12 for everyone regardless of gender. Eckert believes parents should have their children get the HPV vaccine. Most insurance plans fully cover it, and CDC programs exist for families who don’t have insurance or access to vaccines.

“What a gift to give your child—cancer prevention,” Eckert says.

The vaccine can also protect against other cancers caused by HPV such as throat, vulvar, vaginal, penile, anal and rectal cancers, as well as genital warts. While some worry that HPV vaccination will lead to earlier sexual debut or an increased number of sexual partners, there is no research to back up this claim.

“Studies have consistently shown that receiving the HPV vaccine does not alter sexual activity,” says Eckert.

Older teens and adults up to age 26 can also receive the vaccine if they weren’t vaccinated when they were younger. (If you’re between the ages of 27 and 45, you can talk to your doctor about whether getting the vaccine would still be worthwhile.)

Stay on top of your Pap smears and HPV tests

Screening recommendations depend on your age and health. You need to get screened regularly even if you’ve received the HPV vaccine. That’s because the vaccine protects against most but not all HPV types that can cause cervical cancer. Plus, you may have been exposed to HPV before you were vaccinated — the vaccine doesn’t eliminate HPV infections you may already have. Talk to your doctor to determine the best schedule for you.

- Younger than 21 years: Screening is not recommended for this age group, even if you are sexually active, because cervical cancer is extremely rare.

- Age 21 to 29 years: The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends getting your first Pap smear at age 21 and every three years thereafter. The American Cancer Society recommends beginning screening at age 25 with the HPV test and repeating the test every five years. Talk to your doctor about when and what kind of screening you should get — Eckert says the most important thing is getting some kind of screening regularly.

- Age 30 to 65: Get an HPV test every five years or a Pap smear every three years.

- Older than 65: Talk to your doctor to determine if you need to continue with regular screening. If you’ve had regular screenings with normal results and are not at high-risk for cervical cancer, it’s likely you can discontinue screening.

If you are immunocompromised: Get screened more frequently. In particular, Eckert says that HIV and HPV are cunning partners in crime: If you have HIV, you have a six times greater risk of getting cervical cancer from HPV — the development of precancerous changes and cancer is faster.

If the HPV test comes back positive or the Pap shows abnormalities, talk with your doctor so they can get a closer look at what’s going on.

“If you do happen to have a test that’s abnormal, please follow-up,” says Eckert. “It doesn’t mean you have cancer, but we really don’t want you to get cancer.”

Talk to your loved ones about staying up to date

One of the main reasons people don’t get a Pap smear or HPV test is because they don’t know they should be screened or when.

“We can all be advocates. We should all ask people we know, ‘Are you up-to-date on your screening? Has your person had their HPV vaccine?’” Eckert says. “You don’t have to do extreme things to stamp down the stigma. You just have to talk to people.”

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox