In June 2016, more than 20,000 emergency managers in Washington, Oregon and Idaho participated in Cascadia Rising. The four-day exercise was designed to test response and recovery capabilities after a 9.0 magnitude Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami—what has come to be known colloquially as “The Really Big One.” The results: the area is underprepared for a catastrophic earthquake, says Anne Newcombe, R.N., clinical director for emergency services at Harborview Medical Center.

The 620-mile Cascadia Subduction Zone fault line runs off the coast from Cape Mendocino, California to Northern Vancouver Island—and when it ruptures, tsunamis, landslides and extreme shaking damage are expected in the Pacific Northwest.

Seismologists have determined that throughout history, a 9.0 magnitude or greater earthquake occurs on this fault line every 500 years. But that’s just an average: Some have been 1,100 years apart, others 200 years, says Bill Steele, University of Washington seismologist and outreach and education coordinator for the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network. Right now, we’re 317 years into the cycle, which means a magnitude 9.0 quake could happen tomorrow—or not for hundreds of years.

“We’re locked and loaded, but we’re in the very wide window of reoccurrence. So, the earthquake might not happen for a long time, although the closer we get to that average reoccurrence period the more likely it is,” says Steele. “We can’t be complacent about this. It’s clearly a big enough looming hazard that we need to prepare for it now, but there’s no need to panic and we’re not overdue.”

These numbers also don’t take into account the “sneaky magnitude 8s,” says Steele, which would still have a destructive effect on the region. Southern Cascadia has the highest risk to be hit with one of these “partial” Cascadia ruptures. A magnitude 8 or 8.5 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake could still produce a dangerous tsunami and very strong shaking—especially on the coast, where communities may become isolated.

More than 100 miles separate Seattle from where the fault will rupture, which will filter out the highest frequency earthquake waves, but the shaking will still be enough to put the city’s tallest structures at risk, he says.

Double Trouble

What many people don’t realize is that Seattleites aren’t just at risk from one fault line. There is another, the Seattle Fault, which runs directly through the city on an east-west line from the Olympic Peninsula across the Puget Sound and through Alki Point, crossing central Seattle just south of I-90. There is a 5 percent chance of a 6.7 magnitude earthquake on the Seattle Fault in the next 50 years and about a 2 percent chance for an earthquake greater than a magnitude 7.0. If that happens, the damage will be even worse than a magnitude 9.0 Cascadia subduction zone earthquake, Steele says.

“Even well-built structures will be damaged,” he says. In that scenario, the fault would rupture into the Puget Sound, creating additional tsunami issues for the city.

Despite the known risk of earthquakes in the city, most tall bridges and buildings aren’t built to withstand a magnitude 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake. Before 1980, building codes did not require builders to secure houses to their foundation, according to the City of Seattle Office of Emergency Management. In a really big earthquake, older homes that haven’t been retrofitted could slide right off of their foundations, says Steele.

How to Prepare for an Earthquake

Not only is the city’s infrastructure not prepared for a large earthquake, but individuals aren’t doing what they should to protect themselves, either, say Newcombe and Andrew McCoy, M.D., an emergency medicine physician who practices at Harborview. People either view an earthquake as not a real threat or as something so big and hopeless that they don’t know where to begin, they say.

“Most people don’t have any preparations,” says McCoy. “But this is not an if kind of thing, but really a when kind of thing. Obviously no one can tell you when this is going to happen. But it’s something that will happen eventually—and it will be a very bad day in Seattle when it does.”

If you aren’t personally prepared, don’t panic. Instead of succumbing to disaster, there are things you can do to keep yourself safer during an earthquake.

Put together an earthquake kit.

Emergency management groups used to urge people to be prepared to be on their own for three days, but after Cascadia Rising, the recommendation changed to two weeks, says Newcombe.

Purchasing everything you need—including water, food and first aid items—in one go would break most people’s budgets. Instead, McCoy recommends throwing a couple of items in your physical or virtual shopping cart each time you shop for essentials, until you’ve completed your list.

“You don’t have to spend $20,000 and put a bunker in your backyard. You can build this up a little bit at a time,” he says.

Be sure to check your kit every couple years, as some items—like food, water and batteries—have a shelf life.

Get to know your neighbors.

A third of Americans have never interacted with their neighbors, according to a 2015 report released by the Knight Foundation’s City Observatory. That’s not great news in an emergency, says McCoy. You don’t need to exchange holiday gifts or plan vacations with your neighbors, but you should try to learn a few names and be more aware of who you share space with.

“When these things happen, you see neighbors helping neighbors. You see the best in humanity most of the time, and people really turn out and help each other,” says McCoy. “That’s how people successfully make it through a lot of these things.”

Friendly neighbors will be the people you’re able to turn to and share resources with in an emergency. If you have elderly neighbors, they especially may need assistance after an earthquake, whether that means helping make sure they aren’t hurt and are safe from the elements or helping them with medications or contacting family, says McCoy.

Once you’ve connected with your community, there are resources available to help you prepare together. In Seattle, the city’s Seattle Neighbors Actively Prepare (SNAP) program was created to provide tools to help neighborhoods organize to work together in a disaster. There are currently 135 Community Emergency Hubs designated throughout the city where people can gather.

Create a communications plan.

After the initial shock of an earthquake, you’ll want to know that your family is safe. Spending a few minutes now to come up with a plan can save you at least a little panic, says Newcombe.

“Communication and making sure that other people know that you are OK is really, really important,” she says.

Consider setting a designated out-of-state relative or friend who your entire family will contact, says James Lucci, communications supervisor at Airlift Northwest. Local cell networks will be bogged down after an earthquake, and you may not be able to contact your loved ones. You’ll have a better chance at getting a call through to someone out of state, he says. That person can let others in your family know who has contacted them—and can spread the word that you’re OK.

Know where you can get medical care.

After an earthquake, emergency services are going to be extremely busy. Roads may be unpassable or bridges down, and even if an ambulance can make it to you, it likely won’t be immediate, says McCoy. You may need to have an alternate plan for how you’ll get medical assistance if you need it.

If you’re new to the area, familiarize yourself with the hospitals and clinics you can walk to from your home. Fire stations also typically become hubs for medical care after an emergency, so locating the fire stations near you can be helpful, too, he says.

Determine alternate routes and set a meeting point.

Most of us have our typical routes for getting to work or running errands. But earthquake destruction could leave you looking for a new way to get home. Familiarizing yourself with multiple ways home from the places you frequent could help you get home to your loved ones faster, says McCoy.

To that end, having a place where your family can meet if your home becomes damaged can help you make sure everyone is accounted for. This could be a corner down the street, that big rock your family always notices or whatever is memorable, says McCoy.

“Get the kids on board and have everybody understand what the plan is,” says McCoy.

Don’t forget your furry friends.

If you’re a pet owner, it’s important to keep your pet in mind when you’re preparing your emergency kit, says McCoy. That means having extra water stored for your pet and keeping some extra food, waste bags or litter on hand.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has online resources to help pet owners prepare.

Be prepared at work.

Unfortunately, you can’t predict where you will be when an earthquake strikes. And while most people don’t have the space to stockpile food and water at their office, it’s a good idea to keep some items at work, says Newcombe.

This could include extra medication, a sturdy pair of shoes and daily comforts such as a toothbrush and toothpaste, says Newcombe. If you wear contact lenses, consider keeping spare glasses at work. Workplace preparedness should focus on having “small things that will make it more comfortable,” she says.

What to Do After an Earthquake

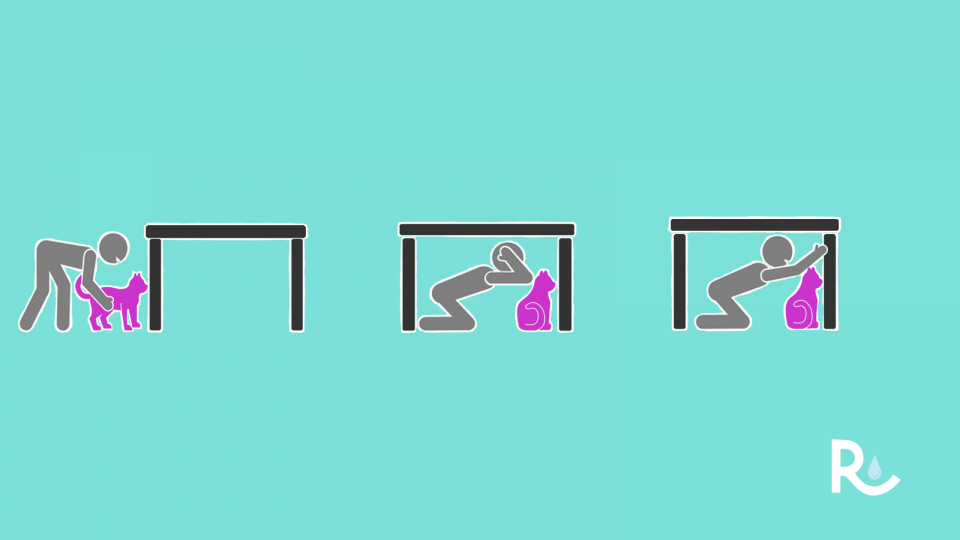

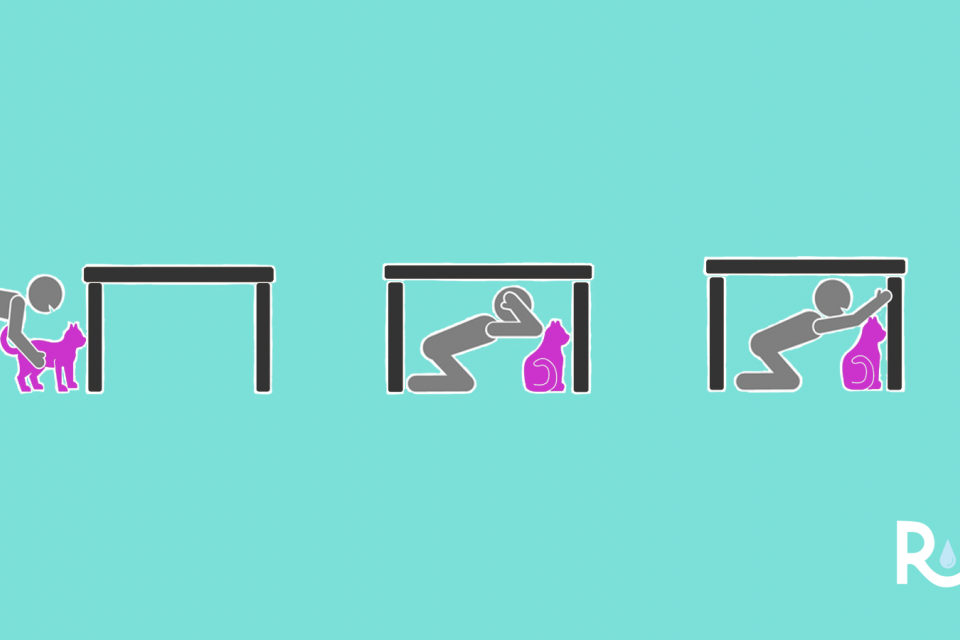

If you feel shaking, drop, find cover and hold on until the shaking stops, says Newcombe. Don’t go outside, and keep in mind that there will be aftershocks, which can be strong.

“Unless the building is coming down, you are safer from falling debris by sheltering under a table and holding onto a table leg rather than going outside,” she says.

Avoid the urge to call 911 immediately unless you truly have an emergency, says Lucci. First responders will be well aware that an earthquake has occurred, and calling with issues that are not immediately life-threatening could delay response to others who need it more.

Once the shaking has stopped, assess the area for damage and make sure you’re in a safe place, says McCoy. If you smell gas at your home, turn it off. If you need medical assistance for cuts or a broken bone, try to get to the nearest facility as quickly as you can. Your communications plan, meeting point and your emergency kit will be important in the hours and days following an earthquake, he says.

Eventually, local and regional emergency responders, FEMA and humanitarian organizations will arrive in the area to help, but it will be weeks or months until life returns to normal, depending on the damage, says McCoy.

“I think people don’t appreciate that they’re really going to be responsible for themselves for a day or two days or three days after this kind of event,” he says. “There aren’t a bunch of magical helicopters that are going to descend to bring water and food. There aren’t a ton of other big cities around, or resource caches ready to open up. You’re going to need to be self-reliant for a little bit of time before the help gets here.”

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox