When you hear the phrase “brain aneurysm” a familiar image probably comes to mind of a medical emergency.

A brain aneurysm is a weak spot in a brain artery. An aneurysm is a medical emergency if it ruptures, but many never rupture.

Unruptured aneurysms often don’t cause symptoms and may not pose a danger, but sometimes they need to be monitored or treated.

Hear from three women who were diagnosed with an unruptured brain aneurysm and learn how they were treated for it — and how they’re doing now.

Guadalupe’s story

In November 2019, Guadalupe Petrone lost her voice — a major problem, since she works in human resources and has to talk a lot for her job.

She went to the doctor, where they did a scan of her neck and head to find the problem — and instead located an aneurysm in her brain.

“The doctor said, ‘You have an aneurysm, and you really need to take care of it,’ and I asked if I was going to die right now because of it and she said no. Then I said, ‘I don’t want to hear it,’ and I hung up on her,” Petrone says.

She was afraid. And she was skeptical. She’d had experiences in the past, when she used to live in California, where she didn’t trust doctors. She didn’t want this to be the same.

A few months later, she got a call from Dr. Louis Kim, chief of neurological surgery at Harborview Medical Center and director of the UW Medicine Brain Aneurysm Center. As it would be for many people who receive a sudden, unexpected diagnosis, Petrone couldn’t wrap her mind around the fact that she had an aneurysm. She asked Kim if it was an error, but he assured her it wasn’t and it was better to get the aneurysm fixed sooner rather than later.

Normally, Petrone says she doesn’t get upset when visiting the doctor, but she panicked, thinking about her daughters and dog and how she would pay for treatment. She asked her daughter to take notes while Kim explained her options. Talking with Shelby Goettle, a patient care coordinator, helped ease her anxieties.

“Dr. Kim helped me realize I needed to pursue treatment. I was gonna ignore it for another 20 years. In Spanish we say ‘cuando te toca, te toca,’ which means when it’s your turn, it’s your turn. But I wanted to be around for my daughters,” she says.

The team found that Petrone’s aneurysm was complex — she says it “looked like a bag of oranges” — which meant they would have to do a craniotomy.

By now, it was November of 2020, and Petrone couldn’t take time off work just yet for recovery — and she was concerned about having surgery during the pandemic. The team reassured her that their COVID-19 safety protocols were robust, so she went ahead and scheduled her surgery day.

Because of those COVID-19 protocols, no one could come with her into the hospital — her daughters dropped her off at the curb. She was wheeled into the operating room alone and scared.

Her procedure went well, and she was touched by the things the team did to comfort her, such as braiding her hair so she wouldn’t lose much of it from the incision. Kim came to visit her regularly while she recovered in the ICU.

“I’m not the most touchy-feely person, but Dr. Kim is amazing, and I wouldn’t have wanted anyone else to do my surgery,” Petrone says.

He also made sure she was up and active as soon as possible, to help build her strength up again and prevent an embolism, plus he looked out for her well-being.

“I was very much pushing for him to let me go back to work in December and he said, ‘No, you need to rest because even though you think that you're doing well, you're still recuperating.’ He was absolutely right,” Petrone says.

Her recovery went well, though with a few hiccups. After surgery, she had trouble hearing in one ear, and for the first few nights she had trouble forming words in English. (Petrone speaks Spanish, English and French.) She couldn’t open her jaw wide, and one night her eye turned red.

As disturbing as these symptoms were, she knew they would get better because Kim and his team had explained them to her ahead of time.

Her eye healed after a week, though it took her jaw a few months to heal. During her last visit with Kim, she asked if she’d need to come back in a year or so for another scan.

“And he said, ‘No, you don’t need to come back. You’re fine. You won’t die from this,’” Petrone says. “And I laughed and said I might have a heart attack or something, but at least my brain will be in great shape.”

Petrone ended up finding out that two of her relatives died of strokes.

“When I was diagnosed, I was really surprised to learn how common aneurysms are,” Petrone says. “Now I like to tell people to check their brains, especially the women in my world.”

Yilin’s story

When Yilin Sun was diagnosed with a brain aneurysm in 2019, she was already dealing with another brain problem: a concussion. Sun, a professor at Seattle Colleges at the time, was teaching in a classroom when a metal bar holding a projector screen broke and hit her in the head.

The concussion, affecting the left side of her brain, was bad enough that she had to retire in order to fully focus on her recovery. The MRI doctors took also revealed an unruptured aneurysm on the right side of her brain, near her right optic nerve.

Sun was referred to Dr. Louis Kim, who talked with her about treatment options. At first she was hesitant. The procedure Kim recommended — endovascular coiling — is minimally invasive, but Sun was afraid she would lose vision in her eye.

“After a lot of consideration, I thought if I didn’t have it treated, my quality of life would suffer. I would always think there’s something like a timed bomb there that I’m not sure when it’s going to rupture. I decided to trust the doctor and go with the procedure. Then I could at least have peace of mind,” she explains.

The procedure and recovering from it ended up being far easier to manage than recovery from her concussion, which caused recurrent headaches, short-term memory problems, focus problems and more.

Three years later, Sun is still recovering from the concussion, but she often “forgets I had an aneurysm” she says, because of how smoothly the process of treating it went.

“Everything went so well. The team at Harborview is amazing, I was under the best care I could possibly have with the amazing Dr. Kim and the neurosurgery team,” she says.

Laurel’s story

It started with fainting. Laurel Baker was in her 30s at the time. Puzzled by this new symptom, she went in to get an MRI and left with a diagnosis: a brain aneurysm. A big one.

“When it’s smaller you can sort of wait and watch. But with the size that mine was, they wanted to refer me to a neurosurgeon,” Baker says.

Baker was shocked. She got the news while she was with her sons, who were 6 and 8 at the time. Emotions overwhelmed her but she tried not to show them so she wouldn’t scare her kids. She had no idea what to expect.

“I think one of the major misconceptions is you hear brain aneurysm and people panic. It’s like this death sentence because most people think of a ruptured brain aneurysm. So there was some confusion for me. I’d never actually heard of somebody having a brain aneurysm that needed surgery that had not ruptured,” she explains.

The referral was for a doctor at Swedish, but her mother’s cardiologist, who works for UW Medicine, recommended that Baker talk to Kim. So, Baker made two appointments.

“Hands down I felt more comfortable with UW Medicine,” Baker says. “Dr. Kim just had this amazing, calming presence and was so knowledgeable. I knew he was my person. I picked my insurance just so that I can see him. He’s above and beyond amazing.”

Baker had a lot of questions about the procedure. She wanted to know what it would entail and what the risks were, if there was a chance the aneurysm could rupture before she could get surgery, and what her prognosis would be after surgery.

“I felt like I was a ticking time bomb even though I knew statistically I wasn’t. But I still felt like I shouldn’t overexert myself or I shouldn’t run too fast,” Baker says.

Kim was able to answer most of her questions during their first meeting, Baker says, which was a relief. (Her previous consultations with Dr. Google unsurprisingly had only provoked anxiety.)

A month after diagnosis, Baker went in for her procedure. Even though her aneurysm was large, treating it didn’t prove to be complicated. Kim used a pipeline embolization device (PED) to block the flow of blood to the aneurysm. After a night of recovery at Harborview, Baker was able to go home.

For a few months after the procedure, she had some vision issues; Kim told her this was because her aneurysm was located near her optic artery. The problem resolved, though, and now Baker is feeling better than ever.

“Even now, when I tell people that I’ve had an aneurysm, you know they're like, Oh my gosh, you lived through it, and I’m like, well, no. I mean, yes, I did live through it, but it never ruptured. So now I live,” she says.

Brain aneurysm basics

Annually only 8 to 10 out of 100,000 people will experience an aneurysm rupture; yet, aneurysms are common, affecting around 6.5 million people in the United States alone.

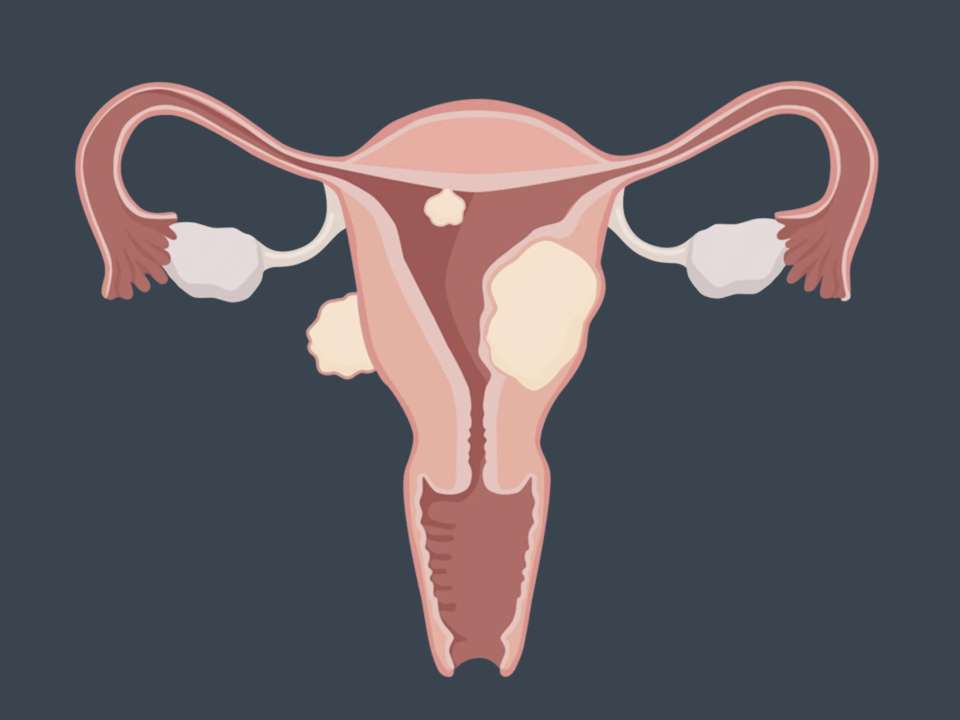

Aneurysms affect women more than men, but many women don’t know much about them and many diagnoses happen incidentally — that is, when a woman goes to the doctor for a different reason and ends up finding out she has an aneurysm.

A brain aneurysm is a bubble-like spot in a brain artery that weakens and fills with blood. Smoking, having high blood pressure, drinking a lot of alcohol, and certain medical conditions put someone at higher risk for developing an aneurysm.

Unruptured aneurysms don’t usually have symptoms. Symptoms of a ruptured brain aneurysm include severe headache, neck stiffness, vomiting, fainting and loss of balance.

Not all aneurysms rupture, but there’s no way of knowing if the aneurysm you have will one day turn into a medical emergency. Since half of ruptured aneurysms are fatal and more than half of people who survive deal with long-term neurological damage, it’s usually safer to get the aneurysm fixed instead of waiting and hoping it doesn’t burst.

There are two main types of procedures used to fix a brain aneurysm: open surgery, which is usually only needed in more complex cases; and endovascular coiling, which is minimally invasive.

Brain aneurysms are scary, but with treatment you can go back to living your life without fear.

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox