Once considered a specialty item, the fizzy fermented tea known as kombucha has in recent years become a staple of refrigerated beverage aisles across the country, especially on the West Coast.

But how did this slightly tart and lightly effervescent fermented beverage come to be considered a health tonic?

“People turn to kombucha for three perceived health benefits: probiotics, antioxidants and B vitamins,” says William DePaolo, a UW Medicine gastroenterologist and director of the Center for Microbiome Sciences & Therapeutics (CMiST).

All about fermentation

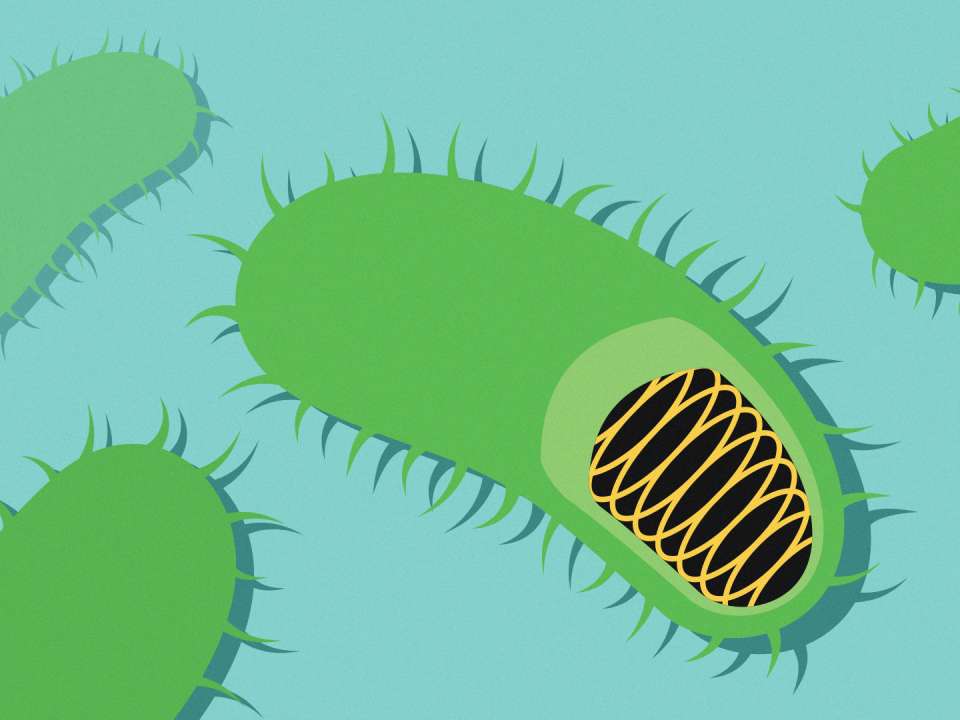

Fermentation is what sets kombucha apart from most other beverages you’ll find in the grocery store cooler. To make kombucha, strains of bacteria, yeast and sugar are added to tea and left to ferment at room temperature. A symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast (known as a scoby) then grows on top of the kombucha, infusing it with flavor.

Next, kombucha is bottled and kept at room temperature for another week or two. Fermentation gives kombucha its tartness and bottling its light carbonation.

Kombucha and probiotics

Along with flavor, kombucha’s fermentation process also infuses it with probiotics. Probiotics are those bacteria — often referred to as the “good bacteria” — that help to keep your gut healthy.

But there’s a catch.

"Thing is, the bacteria from kombucha are unlikely to survive the trip through your stomach,” says DePaolo.

Most bacterial cell walls don’t hold up well in the highly acidic environment that is your stomach. That’s almost always a good thing because your stomach acid kills bacteria that could cause disease.

But along with the bad bacteria go the good bacteria, too. This means that those in kombucha are unlikely to make it to your intestines, where the community of microorganisms known as your microbiome hang out.

There is one rod-shaped bacterium known as Bacillus that is hardy enough to make it through your stomach. But Bacillus just seems to come and go without colonizing or making any change to your existing microbiome, says DePaolo.

“It’s possible the probiotics produce a metabolite that can get through the stomach, but there are no good case-controlled clinical trials that have looked at this question,” says DePaolo.

Kombucha and antioxidants

Remember that the kombucha-making process starts out with a batch of tea, usually green or black.

“Green and black tea have these compounds called polyphenols that have shown great promise in preventing cancer and reducing inflammation in animal studies. Nobody understands how they work, but they seem to,” says DePaolo.

And while kombucha is loaded with antioxidants, it’s because tea is full of antioxidants. Whether the antioxidants in kombucha would perform similarly is not known.

“It’s a reasonable assumption but there aren’t any human-based studies or clinical trials that support it. And it might be simpler and less expensive to get those antioxidants from your tea,” says DePaolo.

Kombucha and B vitamins

Kombucha comes by its high levels of vitamin B the same way it does it probiotics — thanks to the scoby that hangs out on top of it as it ferments.

Unlike bacteria, B vitamins can easily make it through your stomach acid. In fact, stomach acid actually helps with vitamin B12 absorption.

And because your body excretes the B vitamins it doesn’t need in your urine, you don’t have to worry about overdoing it.

However, there are healthier ways to consume B vitamins.

There are whole grains, fruits and vegetables that have high levels of B vitamins but are high in fiber and other nutrients, too.

“You probably wouldn’t want to drink kombucha just to get your B vitamins,” says De Paolo.

Fruits and vegetables beat out kombucha

Turns out mom’s mantra to eat your fruits and veggies is sound advice for promoting a healthy and diverse microbiome.

That’s because fruits and vegetables are full of digestible fibers that feed the friendly bacteria in your gut. For this reason, they’re known as prebiotics.

Unlike probiotics, prebiotics can and do make it through the acidic environment of your stomach. They end up in your intestinal tract, where the bacteria of your microbiome eat the digestible fibers and convert them to other molecules.

“So as they eat, they grow, they reproduce and they expand,” says DePaolo. “Prebiotics accomplish exactly what most people are trying to do when they take probiotic supplements or drink kombucha.”

Healthy ideas for your inbox

Healthy ideas for your inbox